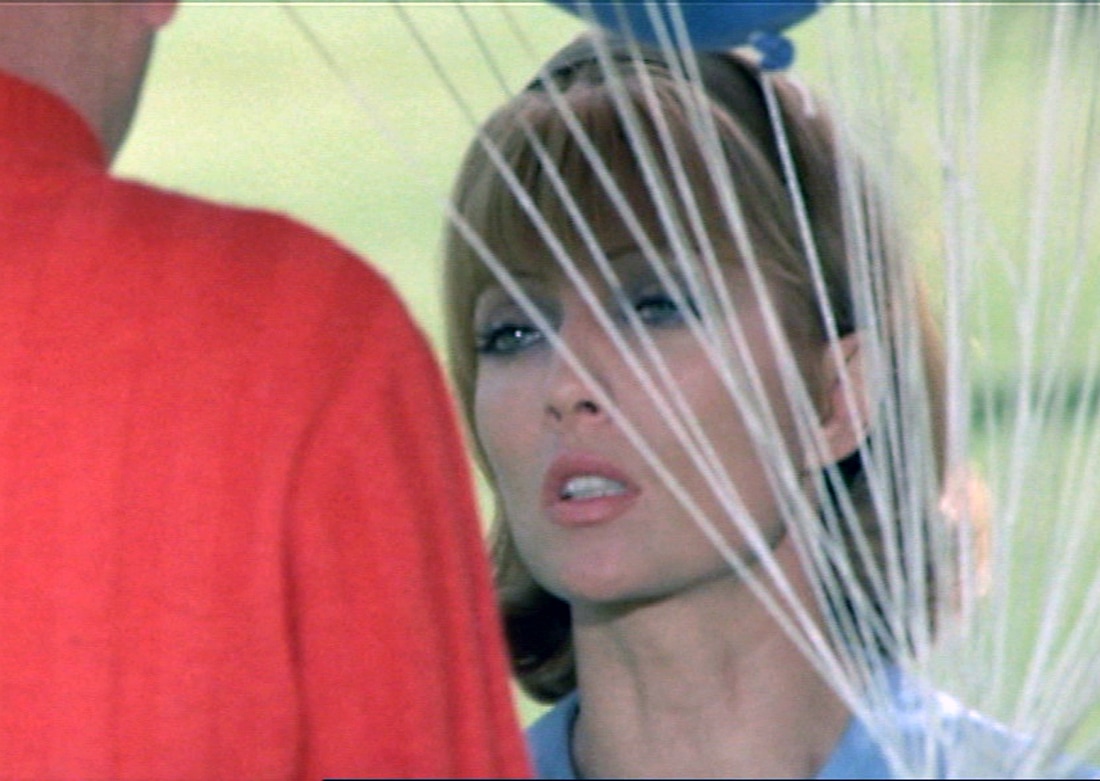

curator's noteThis week, our writers were once again confronted with the task of discussing a film that resides outside the norms of film criticism. The bizarre and at often times difficult to watch LA RUPTURE (Claude Chabrol 1970) creates a hectic, drug-addled experience from start to finish which only increases in confusion as the rules of cinematic editing are loosened throughout its running time. The chaos that ensues will no doubt allow room for an stimulating debate with our writers. BELIEVING BUT NOT SEEINGGEORGE LEEThe theme of perception is quickly established in LA RUPTURE with Charles’ (Jean-Claude Drouot) parents trying to paint Hélène (Stéphane Audran), their daughter-in-law, in a negative light. Their ultimate goal by doing this is to gain custody of their grandson in the proceeding divorce trial. The assumed reason for their negative perception of Hélène is their belief that she is sexually promiscuous. This belief is presented when Helene was revealed to once have been a stripper, but as she describes it: “That didn’t last long”. Helene thinks Charles is a helpful and honest man simply because he is handsome and charming and Charles thinks that the young girl with mental difficulties will be able to be fooled by a simple wig. All these perceptions turn out to be false, leading to the characters varying downfalls with Hélène being betrayed and Charles’ true nature being revealed. LA RUPTURE is undeniably a critique of the bourgeois by painting the rich as evil and manipulative but the way this particular film handles this is to comment on the controlling class’s understanding of perception. What the rich believe as true must be so as they are the ones in power and have the most influence. It is up to Hélène - the representation of the working class - to call them out on their lies. The film was released on the tail end of the French New Wave when perceptions on cinema were changing. The film, therefore, takes a difference route of expression. By the third act, the film diverts away from logical narrative and leans towards surrealism. With the main characters drugged, we are witness to a dream-like sequence from Hélène’s point-of-view. It may not make much sense in contrast to films today but this is the point. We are forced to throw away our existing perceptions of the film and attempt to decide significant elements for ourselves. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch LA RUPTURE on mubi.com until 5 May 2017 and join the discussion!

0 Comments

curator's noteThis week, our writers were once again confronted with the task of discussing a film that resides outside the norms of film criticism. The bizarre and at often times difficult to watch LA RUPTURE (Claude Chabrol 1970) creates a hectic, drug-addled experience from start to finish which only increases in confusion as the rules of cinematic editing are loosened throughout its running time. The chaos that ensues will no doubt allow room for an stimulating debate with our writers. A CLASS OF THEIR OWNMATTHEW WEARSConsidered a master in the mystery genre, Claude Chabrol interwove themes of class struggle and injustice into many films in his catalogue during his golden era. His 1970 experimental melodrama, LA RUPTURE, is certainly no exception to this. The film examines class warfare in an often uncompromising fashion, with the absurdities of the film being an exaggerated social reflection of the class system in France at the time. Mirroring the increased socialist movements within this period, the film is a severe critique on the astonishing power and destructive nature of wealth. Focusing on the custody battle between Hélène Régnier (Stéphane Audran) and her mentally ill husband Charles (Jean-Claude Drouot) over their young son Michel (Laurent Brunschwick), the film offers a strong commentary about the relationship between power and wealth. Money is viewed as a weapon whereby any character that possesses a greater amount is far more capable of obtaining their desire, even to the degree of taking a child from its own mother when it is unwarranted. At no point should the custody of the child be put into question as Hélène is clearly the more competent of the parents. Charles has physically abused both Hélène and Michel, however still stands a chance at being the carer of his child simply because of his rich parents. The film is effective in showcasing the full extent of the power of wealth as the bourgeoisie family are able to use their affluence as a controlling device in order to manipulate Hélène from behind a veil, without her having any knowledge of them doing so. Their money has tainted them and they have lost the virtues that the working class Hélène possesses: integrity, kindness and love. LA RUPTURE is a film that at times can appear quite ludicrous. There are moments where it can be difficult to believe just how far Charles' parents will go in order to gain custody of Michel, often reaching levels whereby they bypass their greedy higher class representations and become nothing short of evil. This film is not just a commentary of the privileged, but rather an outright attack on their morals and ethics. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch LA RUPTURE on mubi.com until 5 May 2017 and join the discussion!

curator's noteThis week, our writers were once again confronted with the task of discussing a film that resides outside the norms of film criticism. The bizarre and at often times difficult to watch LA RUPTURE (Claude Chabrol 1970) creates a hectic, drug-addled experience from start to finish which only increases in confusion as the rules of cinematic editing are loosened throughout its running time. The chaos that ensues will no doubt allow room for an stimulating debate with our writers. HOLY MOTHEREM HOUGHTONLA RUPTURE (Claude Chabrol 1970) sees Hélène (Stéphane Audran) and Charles’ (Jean-Claude Drouot) marriage tested following an argument, culminating in Charles attacking their young son Michel (Laurent Brunschwick) in a violent rage. While Hélène seeks to care for her injured son and save them both from her volatile husband, Charles’ father, Ludovic (Michel Bouquet), goes to extreme lengths to find proof that Hélène is an unfit mother as he attempts to ensure Charles gains custody of his son. There is a lot to be explored in Hélène’s character and her presentation of femininity. She is vulnerable yet courageous; she is strong enough to fight relentlessly for her child, but is able to be emotionally broken just the same as any other person. This duality between courage and vulnerability mirrors the two sides of Hélène the audience is shown. Charles’ parents discover that she was a stripper before she married and it is used as evidence that she is an incompetent mother, even though it was an aspect of her life she chose to put behind her and should not define her identity. This leaves Hélène suspended between two character tropes stereotypically associated with females: the undignified and immoral “whore” and the caring mother. She finds herself in the uncomfortable and unnecessary position of witnessing her past decisions and mistakes manipulate the new life she has chosen for herself and her child. Regardless of her past as a sex worker, Hélène has done nothing wrong. She is presented to the audience as a good-natured and caring mother. However, Charles’ parents continuously criticise and exploit her due to her low social standing and wealth compared to their own. It is this commentary on Hélène’s own femininity that is a truly engaging aspect of LA RUPTURE, as she feels the weight of everyone’s preconceptions about her due to her past as she simply tries to save herself and Michel. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch LA RUPTURE on mubi.com until 5 May 2017 and join the discussion!

curator's noteThis week, our writers were once again confronted with the task of discussing a film that resides outside the norms of film criticism. The bizarre and at often times difficult to watch LA RUPTURE (Claude Chabrol 1970) creates a hectic, drug-addled experience from start to finish which only increases in confusion as the rules of cinematic editing are loosened throughout its running time. The chaos that ensues will no doubt allow room for an stimulating debate with our writers. MENTAL ILLNESS IN LA RUPTURESUMMER MANNINGThe neglect and abuse of mentally ill characters such as Charles and Elise is common in media, with notable examples being WALTER (Stephen Frears 1982) and FORREST GUMP (Robert Zemeckis 1994). A disturbing aspect of LA RUPTURE (Claude Chabrol 1970) is its treatment of mental illness. Charles (Jean-Claude Drouot) is a man struggling with drug addiction and is unable to cope with his illness. Rather than the film following his journey to becoming drug free or learning how to manage his symptoms, the story focuses on how his illness affects those around him. His wife (Stéphane Audran) and father (Michel Bouquet) spend their time blaming each other for his mental state while he is left at home. When he is finally on screen again he tells his wife “It’s as if I’m dead here”, which suggests that he is treated as less than a person, even in his childhood home because of his disability. Another mentally disabled character depicted in LA RUPTURE is Elise (Katia Romanoff), a childlike teenage girl who is taken advantage of. In a harrowing scene (which victims of sexual assault are advised to avoid watching) Paul Thomas (Jean-Pierre Cassel) drugs and kidnaps Elise and takes her to his girlfriend (Catherine Rouvel) who is disguised as Hélène and they force her to watch a pornographic film whilst “Hélène” gropes her. Elise is chosen as a victim because she is vulnerable. She is powerless to stop them whilst under the influence of drugs, and due to her disability is unable to understand the nature of her sexual assault or be able to seek help. When the film was released in 1970 such treatment of those who are mentally disabled was not protested at the time, demonstrating a shift in the reception of mentally ill characters, as the above scene would be a source of contention for modern audiences. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch LA RUPTURE on mubi.com until 5 May 2017 and join the discussion!

curator's noteThis week, our writers were once again confronted with the task of discussing a film that resides outside the norms of film criticism. The bizarre and at often times difficult to watch LA RUPTURE (Claude Chabrol 1970) creates a hectic, drug-addled experience from start to finish which only increases in confusion as the rules of cinematic editing are loosened throughout its running time. The chaos that ensues will no doubt allow room for an stimulating debate with our writers. RUPTURING THE SENSESSTEVEN FEGANLA RUPTURE (Claude Chabrol 1970) begins with a rattle of the senses, living up to its namesake as it subverts the conventions of a slow-burn set-up to the story and instead introduces two of its primary characters in a spectacularly sudden incident. However, before this, the film opens with the foreboding words: “What utter darkness suddenly surrounds me?” spoken by French dramatist Jean Racine who was known for combining elements of comedy and tragedy. These words have instant connotations of unexpectedness and subversion from conventional modes of storytelling as the opening scene plays out and, in hindsight, acts as a warning for the viewer. They also attest to the overall theme of surprise and suspense throughout the film where there is rarely any warning or exposition as to the fate of these characters. We are introduced to our main protagonist Hélène (Stéphane Audran), as she prepares her son’s breakfast. Her husband Charles (Jean-Claude Drouot) stumbles out from another room and without warning or incitement, assaults his wife and subsequently their son (Laurent Brunschwick). This startling event, both for Hélène and the audience, immediately fractures the subtle introduction previously set up to provide an unpredictable series of events that later unfold. The tenacious start to the film immediately poses several questions to the spectator as there is no explanation for Charles’ actions. But before the audience can even begin to speculate the reasons for his sudden burst of violence against his wife, he lifts his son into the air and throws him against a nearby table. At this point, the film surpasses questions of domestic abuse and instead invites the audience to question the unpredictable direction of the film itself. LA RUPTURE sets out to do exactly what its title suggests: rupture the conventions of story set-up and defy the expectations of its audience to provide a fresh and unexpected thriller that never truly explains itself, a trademark style that Chabrol utilised throughout his career. In doing so, it maintains the suddenness and confusion that a breach of any kind usually presents. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch LA RUPTURE on mubi.com until 5 May 2017 and join the discussion!

curator's noteThis week, our writers discuss a film that speaks quietly to its audience and requires the recognition of the quiet intensity of the narrative. SILENCE (Pat Collins 2012) is about a sound recordist, Eoghan (Eoghan Mac Giolla Bhride), who returns to Ireland after 15 years of living in Germany to record areas free of man-made sound. During his quest, he is influenced by folklore and a series of challenging encounters that reflect the intangible silence of his childhood. The film celebrates the beautifully poetic landscape of Ireland and the stories it has to tell. LISTENING OUT FOR HOMEGEORGE LEEIn the film SILENCE (Pat Collins 2012), Eoghan is tasked with returning to his Irish homeland - after being away 15 years - to record sounds free from man-made noise. The purpose of his labour is not disclosed, only that he has been employed to do so. To achieve silence, however, seems futile. To be able to record noises truly free of any man-made sound is unfeasible as, to be able to record sound in general, it requires the use of a man-made machine which in turn makes a sound. Even the most minimal hum of a battery pack prevents silence from being achieved. At one point a man stumbles upon Eoghan and asks "So you’re here?" and Eoghan replies "I am here yeah, but I’m keeping quiet". This conversation seems reminiscent of the old thought experiment: "If a tree falls in the forest and no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound?" Ergo, if Eoghan is there to record it then his presence will prevent the goal of silence. Eoghan seemingly knows that recording silence is impossible, which therefore raises the question of why is he doing it? Or if he really is being employed to do it, what is the purpose of his employer? It seems that this quest for silence is simply an unexplained plot device in order for Eoghan to return home and face his past, as his new life in Berlin acts as an escape from his vague but painful memories of Ireland. Eoghan returning to his homeland is significant as he becomes the tree from the thought experiment. If he is not physically in Ireland, does it continue to exist without his presence? What he slowly learns through the film is that life continues, regardless of if he is there to witness it. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch SILENCE on mubi.com until 26 April 2017 and join the discussion!

curator's noteThis week, our writers discuss a film that speaks quietly to its audience and requires the recognition of the quiet intensity of the narrative. SILENCE (Pat Collins 2012) is about a sound recordist, Eoghan (Eoghan Mac Giolla Bhride), who returns to Ireland after 15 years of living in Germany to record areas free of man-made sound. During his quest, he is influenced by folklore and a series of challenging encounters that reflect the intangible silence of his childhood. The film celebrates the beautifully poetic landscape of Ireland and the stories it has to tell. HOMESICKEM HOUGHTONWhile SILENCE (Pat Collins 2012) does not offer much in terms of a sophisticated narrative, it does provide a thought-provoking exploration of the philosophical concept of “home”. When sound recordist Eoghan (Eoghan MacGiolla Bhríd) returns home to the remote Tory Island after living in Germany for fifteen years, the audience are taken on a journey with him through the poetic sounds of the Irish landscape. As Eoghan searches for sounds that are free from man-made noises, the picturesque settings he ventures to on his travels create the backdrop for a soundtrack provided by nature. A symphony of bird songs, blowing winds and crashing waves all add to Eoghan’s journey home, sounds that were carefully chosen by SILENCE’s sound recordists John Brennan and Eammon Little. Eoghan immerses the audience with the sounds he discovers; they are sounds that create a sense of synaesthesia, engaging more than just one of the senses by pulling the listeners to these locations. The scenes where Eoghan is at one with the landscape and listens to the sounds of the natural world are especially immersive and three-dimensional. You can almost feel the wind brushing against you as birds fly over head and sing to one another. It is incredibly relaxing to hear, evoking a sense of safety akin to that felt by being somewhere you can call home. It is a nostalgic feeling, especially if it you grew up in a similarly rural setting. Rather than representing the physical home that Eoghan returns to, it audibly symbolises the familiarity and safety felt when reminiscing about where you have come from. It makes the film more powerful; as Eoghan is transported home, so are the audience. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch SILENCE on mubi.com until 26 April 2017 and join the discussion!

curator's note This week, our writers discuss a film that speaks quietly to its audience and requires the recognition of the quiet intensity of the narrative. SILENCE (Pat Collins 2012) is about a sound recordist, Eoghan (Eoghan Mac Giolla Bhride), who returns to Ireland after 15 years of living in Germany to record areas free of man-made sound. During his quest, he is influenced by folklore and a series of challenging encounters that reflect the intangible silence of his childhood. The film celebrates the beautifully poetic landscape of Ireland and the stories it has to tell. TALKING IN SILENCEMATTHEW WEARSContrary to what the title would suggest, SILENCE (Pat Collins 2012) is a film in which sound plays an equally important role as to its absence. Although the film follows the brooding Eoghan (played by co-writer, Eoghan Mac Giolla Bhride) and his quest for quiet, it is through dialogue that the secrets to this film are unlocked. Seemingly random encounters occur throughout this pensive piece of filmmaking and the conversations had during these moments act as our guide through the often ambiguous narrative. This is an extremely personal film and with each new character a new concept or snippet of information is unveiled. These interactions allow for Eoghan’s conscience to slowly be exposed as well as allowing us to delve deeper into his memories. The information gives the audience a framework to better understand the film. This is explicitly demonstrated in the scene in which Eoghan joins a local man for a drink in his mother's house. Together, they talk of philosophical theories which re-contextualise what silence could actually represent. Here, it is perceived as a concept achievable only prior to birth or after death. It is perhaps the most crucial scene in the film, allowing the audience to view silence as something other than an objective of tranquillity. It can also be seen as devoid of any life or existence. The conversation that takes place is extremely free-flowing and natural, making it hard to determine where "documentary" ends, and "drama" begins. SILENCE is a film that requires the utmost attention to the dialogue and themes being discussed in order to interpret the narrative. Without these pivotal pieces of information, the film becomes nothing more than an assortment of bleak images, perhaps only fully understood by the writer himself. The brief exchanges throughout act as the glue to produce a coherent, thought-provoking film. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch SILENCE on mubi.com until 26 April 2017 and join the discussion!

curator's noteThis week, our writers discuss a film that speaks quietly to its audience and requires the recognition of the quiet intensity of the narrative. SILENCE (Pat Collins 2012) is about a sound recordist, Eoghan (Eoghan Mac Giolla Bhride), who returns to Ireland after 15 years of living in Germany to record areas free of man-made sound. During his quest, he is influenced by folklore and a series of challenging encounters that reflect the intangible silence of his childhood. The film celebrates the beautifully poetic landscape of Ireland and the stories it has to tell. THE SOUND AND THE SILENCESUMMER MANNINGThere is one scene in SILENCE (Pat Collins 2012) that manages to encapsulate its entire story. While on the surface, SILENCE is about a man searching for a place without manmade noise, its true story is about returning to one’s past. When an unnamed man invites him to his mother’s old house, Eoghan (Eoghan Mac Giolla Bhride) sings an old Tory Island ballad named “A Pháidí, a Grá’Trad” and provides the song’s context. The song was written by a young woman who wanted to use it to stop her beloved from emigrating, but was unsuccessful. The background of the song has a clear significance to him, as he states “Unless you know the story behind it, you don’t know what it’s about.” This one line summarises his own journey within the film, as the audience knows little about his life in Berlin, and so does not know his true motives in returning to his childhood home. The film presents differing views on living in this childhood town. Eoghan wants to explore the world, as does a young boy he encounters who plans to move to the mainland for study. The unnamed man refers to his life on a small island as “the biggest infinity possible”, saying he feels “rooted”; a sentiment echoed by the other islanders Eoghan encounters. A view of the kitchen window looking out to the garden illustrates this perspective beautifully. The man walks out of a static shot, symbolising how he left his childhood home. After some time, he eventually returns to the shot: it is a visual depiction of his return to his mother’s home after her death. The camera lingers, signifying how the home he left will always remain the same, even if he has changed. The shot focuses on the background, where there is a huge tree with an old tyre swing attached to it. It is a tangible symbol of the childhood he now misses, and the life he returns to every time he comes back to his mother’s house. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch SILENCE on mubi.com until 25 April 2017 and join the discussion!

curator's noteThis week, our writers discuss a film that speaks quietly to its audience and requires the recognition of the quiet intensity of the narrative. SILENCE (Pat Collins 2012) is about a sound recordist, Eoghan (Eoghan Mac Giolla Bhride), who returns to Ireland after 15 years of living in Germany, to record areas free of man-made sound. During his quest, he is influenced by folklore and a series of challenging encounters that reflect the intangible silence of his childhood. The film celebrates the beautifully poetic landscape of Ireland and the stories it has to tell. THE HEART OF SILENCESTEVEN FEGANA thread of nostalgia runs through SILENCE (Pat Collins 2012) like a breadcrumb trail as sound recordist Eoghan makes his way back home for a job from the busy, man-made city sounds of Berlin. Attempting to capture the sounds of nature untouched by man in his native Irish countryside, Eoghan interacts with a variety of people who ironically interrupt his quest for silence. He remains unfazed by their appearance and they ultimately implore him to search his past. The nostalgic thread remains prominent in these instances and drives the narrative. Eoghan intently listens to the stories that the locals have to tell about their experiences involving sound and silence. The stories are deliberately intertwined with Eoghan’s quest as he aims to discover true silence for himself. The breathtaking landscape that Eoghan traverses throughout the film becomes a character in itself and a companion to Eoghan. He often sits still with his headphones on and boom mic placed in the ground, capturing the sounds of nature that are not man-made. It is a landscape that Eoghan is familiar with but is now seeing with a new-found sense of appreciation after his time in the city. The dramatic and unnerving beauty of the scenery takes Eoghan’s hand and leads him into the past where he is more content listening to the stories of the locals than sitting with his sound equipment in solitude. In these moments, the film utilises the flowing rivers and vast mountains to help Eoghan discover what he is looking for. At first this may have been to record natural sound but, as the film unfolds and Eoghan treads deeper into these once familiar lands, his nostalgic desires force him to reminisce about his childhood in the forgotten landscape and his journey finds him at his old family home. The scenery acts as a tour guide, leading Eoghan to various avenues in his past where the differences between silence and peace become blurred and Eoghan’s interpretation of silence becomes unclear. Although he enjoys his interactions with the locals surrounding his picturesque home, he ultimately will not find what he is looking for without first re-discovering what led him away and then back again to where his heart truly lies. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch SILENCE on mubi.com until 25 April 2017 and join the discussion!

|

MUBIVIEWSOne MUBI film, five perspectives, endless possibilities. Archives

July 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed