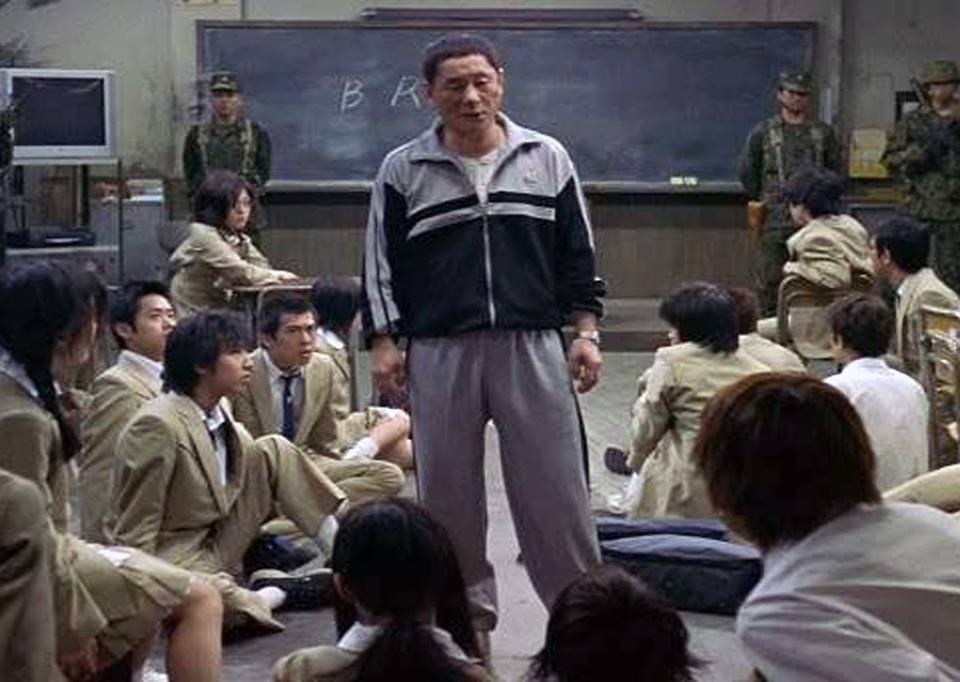

curator's noteThis week our writers delve deep into the brutal fight for survival in their exploration of Kinji Fukasaka's Japanese teen-horror BATTLE ROYALE (2000). THE GAMES WE PLAYEm HoughtonRespect for one’s elders is an important cultural attitude in Japan and, as the opening scenes of BATTLE ROYALE (Kinji Fukasaku 2000) tell us, delinquent school children have become a serious issue in this dystopian world. This exasperating refusal to follow the rules set out by the older generation results in the BR Act being passed, whereby students are forced to battle to the death until only one remains. By doing so, the film acts as a metaphor for how many young people living in the world feel; they can all too often feel helpless in a world controlled by adults. Graphic violence between children always makes for shocking viewing in both cinema and literature. Examples include the death and subsequent cannibalistic consumption of Piggy in THE LORD OF THE FLIES (Harry Hook 1990) as well as the more contemporary issues presented in THE HUNGER GAMES series (Gary Ross and Francis Lawrence, 2012-). BATTLE ROYALE’s violence is considered more extreme than many other examples, with intensely graphic death scenes as classmates settle old school-born scores. The violence in BATTLE ROYALE questions ethics and morality of adolescents as some children fully participate in The Games and aim to kill as many others as possible, while others refuse to partake and resort to suicide. The film creates a powerful dichotomy of peace and chaos; amongst the harrowing violence, death and destruction the children form friendships and even romances with each other. Child violence is always viewed as shocking when displayed on screen as it challenges normal societal expectations for how children should act. It is even more so, when the children are becoming violent as an act of rebellion against the adults holding them to these expectations. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch BATTLE ROYALE on mubi.com until 30 May 2017 and join the discussion!

0 Comments

curator's noteThis week our writers delve deep into the brutal fight for survival in their exploration of Kinji Fukasaka's Japanese teen-horror BATTLE ROYALE (2000). TEEN QUEENS AND WANNABESSummer ManningWhile "Teen Queens and Wannabes" may not be expected when reading an article about the Japanese dystopian horror BATTLE ROYALE (Kinji Fukasaku 2000), the name of Rosalind Wiseman’s 2002 self-help book, which was adapted by Tina Fey to create the satirical teen comedy MEAN GIRLS (Mark Waters 2004), serves as an apt comparison. Both films comment on the hierarchical social structure of high school. While MEAN GIRLS illustrates the social order with Cady Heron (Lindsay Lohan) imagining the girls who emotionally manipulate each other as wild animals in the African plains, BATTLE ROYALE demonstrates it with a literal fight to the death. One clear parallel that can be drawn is in the BATTLE ROYALE character Mitsuko (Kou Shibasaki) and MEAN GIRLS antagonist Regina (Rachel McAdams). Cold, manipulative and dangerous, both girls lack true friends and distance themselves as a means of self-preservation. While Regina has untreated anger management issues and has trouble coping with her parents fighting, Mitsuko killed a man who paid to have sex with her at a young age and has had to live with the trauma from this experience. Both characters exercise their power over other students as a coping mechanism, so that they can have control over something in their lives. Noriko Nakagawa (Aki Maeda) is bullied by a group of girls in her school, who lock her in a bathroom stall that has defamatory graffiti written about her on the wall. She is devastated when her friend Megumi (Sayaka Ikeda) is murdered by Mitsuko, leaving her without a female friendship, a bond that is crucial to growing young women. This is the opposite to Cady’s journey in MEAN GIRLS, where she becomes one of the bullies and uses her popularity to overthrow Regina. When the North Shore High School students discover that she was involved in writing hate messages in a Burn Book and stage a revolt, she is ostracised and hides from everybody in a bathroom cubicle to eat her lunch. Both films highlight the need for young people to develop healthy social relationships with their peers, as well as the psychologically damaging consequences of bullying and isolation, and they act as cautionary tales against fighting with classmates. Adolescence is difficult enough without starting wars, whether literal or figurative. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch BATTLE ROYALE on mubi.com until 30 May 2017 and join the discussion!

curator's noteThis week, our writers discuss a film that speaks quietly to its audience and requires the recognition of the quiet intensity of the narrative. SILENCE (Pat Collins 2012) is about a sound recordist, Eoghan (Eoghan Mac Giolla Bhride), who returns to Ireland after 15 years of living in Germany to record areas free of man-made sound. During his quest, he is influenced by folklore and a series of challenging encounters that reflect the intangible silence of his childhood. The film celebrates the beautifully poetic landscape of Ireland and the stories it has to tell. THE SOUND AND THE SILENCESUMMER MANNINGThere is one scene in SILENCE (Pat Collins 2012) that manages to encapsulate its entire story. While on the surface, SILENCE is about a man searching for a place without manmade noise, its true story is about returning to one’s past. When an unnamed man invites him to his mother’s old house, Eoghan (Eoghan Mac Giolla Bhride) sings an old Tory Island ballad named “A Pháidí, a Grá’Trad” and provides the song’s context. The song was written by a young woman who wanted to use it to stop her beloved from emigrating, but was unsuccessful. The background of the song has a clear significance to him, as he states “Unless you know the story behind it, you don’t know what it’s about.” This one line summarises his own journey within the film, as the audience knows little about his life in Berlin, and so does not know his true motives in returning to his childhood home. The film presents differing views on living in this childhood town. Eoghan wants to explore the world, as does a young boy he encounters who plans to move to the mainland for study. The unnamed man refers to his life on a small island as “the biggest infinity possible”, saying he feels “rooted”; a sentiment echoed by the other islanders Eoghan encounters. A view of the kitchen window looking out to the garden illustrates this perspective beautifully. The man walks out of a static shot, symbolising how he left his childhood home. After some time, he eventually returns to the shot: it is a visual depiction of his return to his mother’s home after her death. The camera lingers, signifying how the home he left will always remain the same, even if he has changed. The shot focuses on the background, where there is a huge tree with an old tyre swing attached to it. It is a tangible symbol of the childhood he now misses, and the life he returns to every time he comes back to his mother’s house. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch SILENCE on mubi.com until 25 April 2017 and join the discussion!

|

MUBIVIEWSOne MUBI film, five perspectives, endless possibilities. Archives

July 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed