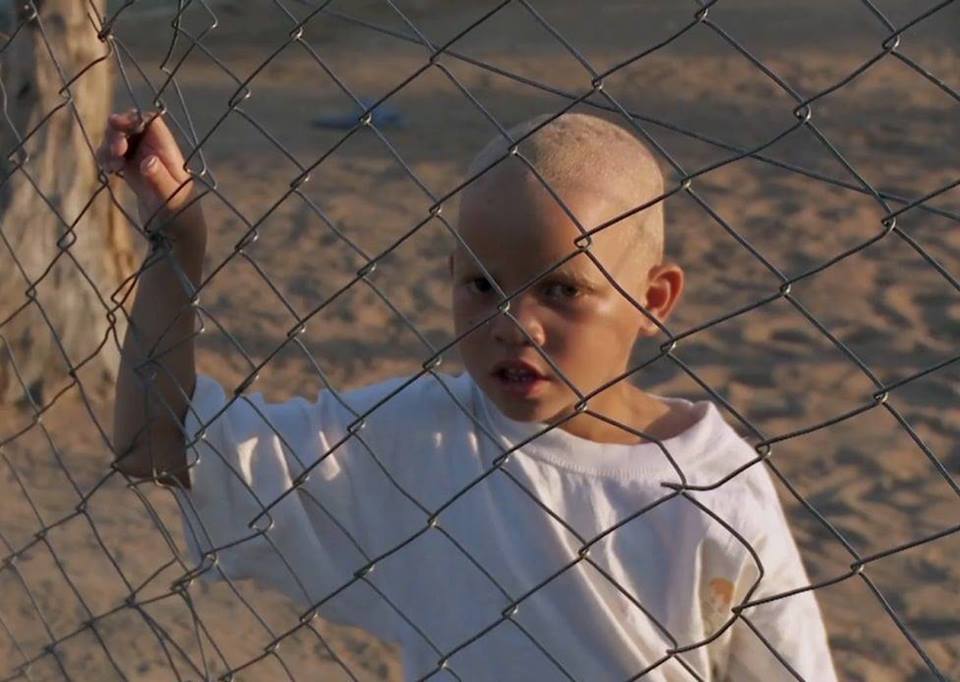

curator's noteFor the final MUBIVIEWS of the summer, our writers to consider Vic Sarin’s THE BOY FROM GEITA (2014), a harrowing documentary that examines albinism within Tanzanian culture and the people that are persecuted because of it. TANZANIAN DEVILSSTEVEN FEGANAt its core, THE BOY FROM GEITA (Vic Sarin 2014) explores the personal struggle of Tanzanian individuals who suffer from Albinism. However there are wider implications of the documentary that suggests that the government is complicit in the sale of albino body parts and therefore a more serious issue of potential corruption throughout the East African region is presented. The documentary for the most part follows teenager Adam Robert, whose hands were mutilated and sold to witch doctors as it is believed that the body parts of those with Albinism will bring good fortune. By having the narrator speak candidly with Adam and other members of his community, the documentary provides a personal account and this inevitably resonates to a far greater extent than focusing on potential government involvement alone. By doing so, the documentary sheds light on an issue that may not have been as prominently covered in the media before and exposes the murdering of albino people throughout Tanzania and wider Africa. Adam's personal story is prevalent throughout the documentary and it is the young boy’s lack of actual dialogue that makes his plight that much more sorrowful. Instead of addressing the brutal attack that left him without several fingers, the documentary instead focuses on Adam’s personal life goals and ambitions and even goes so far as to re-enact dreams and nightmares that the young boy has. By doing so, we are drawn into Adam’s life and are along for the journey to America where he is due to get a life-altering operation. Ultimately, what we can see carries far greater emotional impact than what we are told. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch THE BOY FROM GEITA on mubi.com until 13 July 2017 and join the discussion!

0 Comments

curator's noteThis week our writers delve deep into the brutal fight for survival in their exploration of Kinji Fukasaka's Japanese teen-horror BATTLE ROYALE (2000). SOCIETY'S BATTLEMATTHEW WEARSReleased at the start of the millennium, BATTLE ROYALE (Kinji Fukasaka 2000) explores multiple issues that were at the forefront of concern for Japanese society. Even today the film holds just as potent a message about youth and a society addicted to violence. The film's premise - school children fighting to their death - can at first appear to be totally absurd. But as with other socio-political horrors, such as DAWN OF THE DEAD (George A. Romero 1978) and THE HOST (Bong Joon-Ho 2006), this initially unrealistic concept works in its favour. The film presents a world filled with insanity and, most disturbing of all, a world that is not too far away from our own. Commenting on western society's relationship with violence, the film uses excessive bloodshed, overly-malicious characters and inventive weapons such as tasers and crossbows to create a world in which humans must commit the worst atrocities in order to survive. The most disheartening aspect is just how fast a person's character and morals can change when their own interests are at stake, displayed at its most extreme when Kazushi Nîda (Hirotito Honda) viciously shoots Yoshio Akamatsu (Shin Kusaka) with a crossbow in the first few minutes of the battle. BATTLE ROYALE is a film that asks the audience to consider how far they would go to survive in the same situation but also how far society would go when faced with equally difficult problems. The film highlights the inexcusable lack of humanity that already exists within our everyday culture and acts as a forewarning for what is seemingly imminent. The film is a harrowing depiction of a bleak future, a future where all our current failures are maximised to their fullest. Most harrowing of all is the lack of alternative choices that the film gives us. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch BATTLE ROYALE on mubi.com until 30 May 2017 and join the discussion!

curator's noteThis week our writers delve deep into the brutal fight for survival in their exploration of Kinji Fuasaka's Japanese teen-horror BATTLE ROYALE (2000). AN AGE-OLD BATTLESTEVEN FEGANThe young-adult dystopian movie boom of the past ten years in mainstream cinema has often followed similar tropes that have proven successful, both financially and through audience reception. Films such as THE HUNGER GAMES (Gary Ross 2012) and THE MAZE RUNNER (Wes Ball 2014) have depicted dystopian worlds where the teen heroes are the puppets and the adults are their puppet masters. BATTLE ROYALE (Kinji Fukasaku 2000) uses a similar approach and was one of the first to do so. Following the release of THE HUNGER GAMES, the Japanese film ushered in an age of young versus old and has seen a resurgence in popularity; it was the exceedingly violent film that mainstream audiences had hoped THE HUNGER GAMES would be. BATTLE ROYALE includes metaphorical undertones of young people navigating an adult-controlled world to create a relatable, albeit excessive, version of contemporary society. Here, decisions about the future lie in the hands of adults. The young have little choice but to follow. Part of the enduring appeal of films such as BATTLE ROYALE stems from placing young adults as the protagonists, guaranteeing a large demographic. It also represents their insecurities as children in an adult-controlled world that is presented in a highly stylised, dystopian environment created by adults. This is not too dissimilar to modern society where decisions are made by an older generation yet it is the youth who will ultimately navigate the world that has been created for them. With rumours of censorship in various countries including the US and Canada, BATTLE ROYALE remains a relevant film from a societal perspective since its mainstream resurgence. Banned to anyone under the age of 15 after its release in Japan, the film's controversial themes and its difficulty in reaching a mainstream audience only solidify its cultural significance. Such censorship is controlled by adults; the primary demographic - young adults - suffer the consequences as a result. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch BATTLE ROYALE on mubi.com until 30 May 2017 and join the discussion!

curator's noteThis week, our writers were once again confronted with the task of discussing a film that resides outside the norms of film criticism. The bizarre and at often times difficult to watch LA RUPTURE (Claude Chabrol 1970) creates a hectic, drug-addled experience from start to finish which only increases in confusion as the rules of cinematic editing are loosened throughout its running time. The chaos that ensues will no doubt allow room for an stimulating debate with our writers. A CLASS OF THEIR OWNMATTHEW WEARSConsidered a master in the mystery genre, Claude Chabrol interwove themes of class struggle and injustice into many films in his catalogue during his golden era. His 1970 experimental melodrama, LA RUPTURE, is certainly no exception to this. The film examines class warfare in an often uncompromising fashion, with the absurdities of the film being an exaggerated social reflection of the class system in France at the time. Mirroring the increased socialist movements within this period, the film is a severe critique on the astonishing power and destructive nature of wealth. Focusing on the custody battle between Hélène Régnier (Stéphane Audran) and her mentally ill husband Charles (Jean-Claude Drouot) over their young son Michel (Laurent Brunschwick), the film offers a strong commentary about the relationship between power and wealth. Money is viewed as a weapon whereby any character that possesses a greater amount is far more capable of obtaining their desire, even to the degree of taking a child from its own mother when it is unwarranted. At no point should the custody of the child be put into question as Hélène is clearly the more competent of the parents. Charles has physically abused both Hélène and Michel, however still stands a chance at being the carer of his child simply because of his rich parents. The film is effective in showcasing the full extent of the power of wealth as the bourgeoisie family are able to use their affluence as a controlling device in order to manipulate Hélène from behind a veil, without her having any knowledge of them doing so. Their money has tainted them and they have lost the virtues that the working class Hélène possesses: integrity, kindness and love. LA RUPTURE is a film that at times can appear quite ludicrous. There are moments where it can be difficult to believe just how far Charles' parents will go in order to gain custody of Michel, often reaching levels whereby they bypass their greedy higher class representations and become nothing short of evil. This film is not just a commentary of the privileged, but rather an outright attack on their morals and ethics. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch LA RUPTURE on mubi.com until 5 May 2017 and join the discussion!

curator's noteFor the MUBIVIEWS debut film we wanted to challenge our writers by discussing the sensitive topic of gender exploration, which is so rarely seen from a child’s point-of-view. The film in question is French social realist drama TOMBOY (Céline Sciamma 2011) about a ten-year-old tomboy who passes as a boy to her friends throughout the course of the summer. The unfamiliar setting for the protagonist Laure (Zoé Héran) allows her to safely experiment with her gender through her persona Mickäel. The film tackles isolation, identity and friendship in a tone which MUBI itself describes as ‘delicate and insightful’ highlighting the innocence behind the film. REALISING THE ISSUESGEORGE LEESocial realism is a film genre which brings to the forefront members of society that are often underrepresented. TOMBOY (Céline Sciamma 2011) uses social realist techniques to tell a story of the exceptional nature of the everyday. From its use of handheld cameras to the contemporary setting, the film remains within the boundaries of realism. Social realism often comes hand in hand with a strong political message that the filmmaker feels must be brought to attention and, in the case of TOMBOY, it is the politics of experimenting with gender and sexuality through the perspective of a ten-year-old. Social realism often avoids the use of a mainstream narrative structure. This is very apparent in TOMBOY where the film does not have a succinct ending; it feels as though it never leaves the second act. This can be seen as a metaphor for the experience of transgender children where they feel something is disjointed about their lives. A significant line is where Laure’s mother asks her: “Got an idea? Cos if you do, please say so, I can’t think of any. Have you got a solution?”. This is a shocking statement because it reveals that there is a lack of support system in place if Laure decided that she does in fact identify as a boy. Even if there was, it is questionable that a ten-year-old would be aware of the level of support in place for people that are transgender. The use of handheld camera positions us in relation to Laure’s childlike point-of-view so her confusion is that much more impactful. The point the film is trying to make is that these issues need to be discussed from a young age to increases awareness and subsequently highlight the issue in society. The use of social realism as a storytelling technique really cements this and makes the film less of an entertainment piece but an honest critique of our current societal position. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch TOMBOY on mubi.com until 3 April 2017 and join the discussion!

|

MUBIVIEWSOne MUBI film, five perspectives, endless possibilities. Archives

July 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed