curator's noteFor the final MUBIVIEWS of the summer, our writers to consider Vic Sarin’s THE BOY FROM GEITA (2014), a harrowing documentary that examines albinism within Tanzanian culture and the people that are persecuted because of it. OTHERINGGEORGE LEEOthering is a process in which a majority of people are treated as ‘us’ and the remaining minority are seen as ‘them’. The ‘them’ are then referred to in less than human terms and treated as completely alien from the seemingly normal society. They are no longer seen as people but ultimately seen and therefore treated as less than. Othering is often applied to a member of society who does not adhere to societal norms. This is often the case in cinema which has a long a sordid history of enhancing these stereotypes, from early cinema’s treatment of women to recent African American representation. The film THE BOY FROM GEITA (Vic Sarin 2014) attempts to not only highlight these issues but show them in an honest and subsequently horrifying light. The film follows a young Tanzanian boy, Adam and his persecution for being an Albino. The film focuses heavily on this aspect of othering. The characters in the film tell their stories of how in Tanzania albinos are especially vulnerable to persecution. These scenes are heartbreaking as the children experienced truly atrocious events but even more so is their complete confusion as to why they are being discriminated against. Adam is violently attacked, all because he is deemed as different. In this particular case, his attackers violent remove his limbs as they are under the impression that body parts of Albino people contain magical powers. Rather than delving into this belief, the film chooses to focus on the futility of othering, that no one is really that different and much less so should be in any form persecuted for it. It does a fantastic job of showing the albino characters' humanity as they themselves try to come to grips with why they are being persecuted for something they have no control over. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch THE BOY FROM GEITA on mubi.com until 13 July 2017 and join the discussion!

0 Comments

curator's noteFor the final MUBIVIEWS of the summer, our writers to consider Vic Sarin’s THE BOY FROM GEITA (2014), a harrowing documentary that examines albinism within Tanzanian culture and the people that are persecuted because of it. NOT SO BLACK AND WHITEMATTHEW WEARSDocumentaries have the unique ability to expose topics that otherwise do not get the attention they deserve. They employ narrative techniques that present their audience with a character or characters that fit into a grander theme. Vic Sarin’s harrowing and uncompromising THE BOY FROM GEITA (2014) does exactly this. However, the documentary struggles to make what should have been an engaging, captivating story into a cohesive piece of work. Difficult editing is arguably the film’s most problematic characteristic, with a lack of focus causing major issues throughout. Many sequences and characters are either hard to follow, or just hard to understand why they made their way into the film in the first place. There are two distinct halves to the documentary with the first following Adam Robert’s tragic life of unimaginable abuse and injustice due to his albinism, whilst the latter half focuses on the intervention of wealthy Canadian entrepreneur, Peter Ash, who also has the same condition. The jump between the two separate characters can be jarring and it is confusing as to what the main focus of the film is. This confusion is increased with the addition of other characters, such as an older male whose introduction at the beginning of the film would have the audience believe he would be a pivotal character throughout. This is also the case for the mother who lost both arms in a horrifically barbaric attack. While her story is shocking, her character is not developed fully at all and, after her story is told, she fades into obscurity. Despite its flaws, THE BOY FROM GEITA still manages to engage its audience enough to get the core message of the film across. The stories are devastating to the point where it is hard to believe they are true, and the film’s unrelenting approach to graphic images only adds fuel to its fight. It must be commended for bringing such a specific and painfully under-discussed topic to light for Western audiences, but could have been executed in a far more cohesive manner in order for it to reach its full potential. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch THE BOY FROM GEITA on mubi.com until 13 July 2017 and join the discussion!

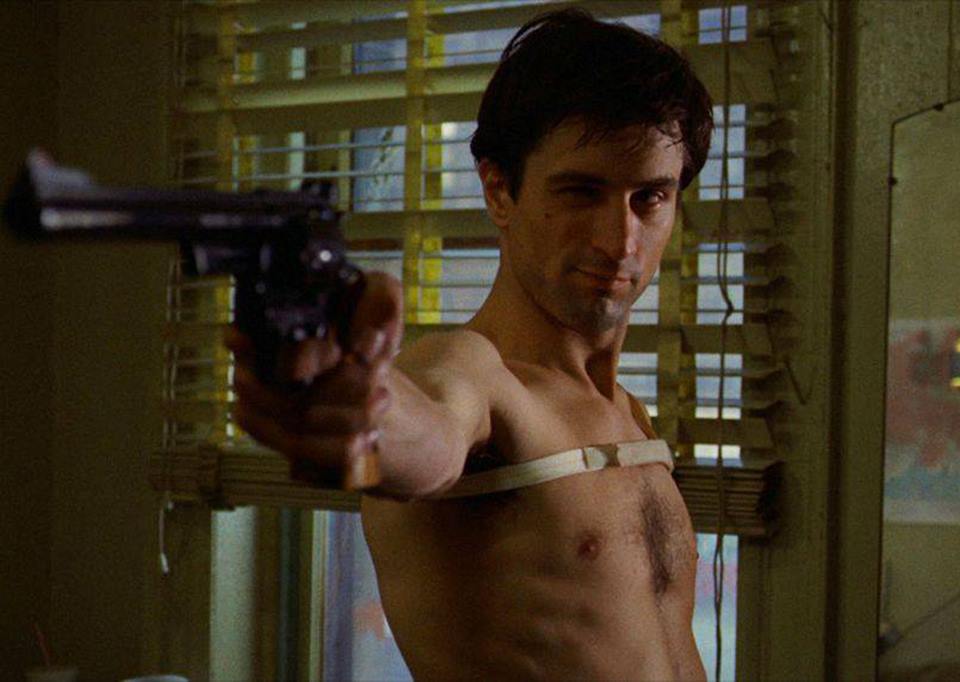

curator's noteThis week our writers return to MUBIVIEWS with the classic American vigilante film TAXI DRIVER (Martin Scorsese 1976). As a regular favourite on lists of the greatest film of all time, what will our writers make of this critically acclaimed Neo-noir. TAXI FOR ONEMatthew WearsLoneliness is a theme that can be extremely difficult to portray on the silver screen as it often relies entirely on both the actors performance and the space given to them by the camera to allow an audience to fully understand a character’s feelings. Director Martin Scorcese explores this masterfully and extensively in his 1976 neon-laced noir, TAXI DRIVER, a film where cinematography plays an enormous role in creating the distance between Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro) and the gloomy, bleak streets of 1970s New York City. Michael Chapman’s camera work constantly emphasises Bickle’s isolation within his surroundings, using techniques and shots that shows him to be the outsider that he believes himself to be. The film is doused in shots that directly inform the complex, twisting narrative, however none more intriguing than the slow and rather unconventional tracking shot in which Travis pleads to Betsy (Cybil Shepherd) to give him a second date having spectacularly blown his first one. The camera shifts from initially framing Travis, tracking right until he is left off screen to show nothing other than a dull, desolate hallway leading out into the dark and dangerous New York streets. This is a visual representation of the remoteness that Travis feels, even when surrounded by one of the most iconic cities he finds himself alone. He is around the corner, hidden from the outside world, perhaps a metaphor questioning the ex-marine’s sense of existence after serving in the Vietnam war. TAXI DRIVER is a film created with such astounding attention to detail, that every shot can be analysed in order to gain a greater understanding of the psyche of enigmatic anti-hero, Travis Bickle. Every shot has significance in constructing the warped and lonely world in which he lives, and only a handful of films use camerawork in such a visually expressive manner. It is for this reason that this landmark New-Hollywood film projected both director and lead into stardom, cementing itself as one of the most enthralling character studies ever produced. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch TAXI DRIVER on mubi.com until 4 July 2017 and join the discussion!

curator's noteThis week our writers return to MUBIVIEWS with the classic American vigilante film TAXI DRIVER (Martin Scorsese 1976). As a regular favourite on lists of the greatest film of all time, what will our writers make of this critically acclaimed Neo-noir REFLECTING INSANITYSteven FeganIsolation is the most prominent and recurring theme throughout TAXI DRIVER (Martin Scorsese 1976) and Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro) is a lonely and detached outcast throughout the film. In what is arguably the film’s most iconic scene, Travis practises with a gun in the mirror, evidence of his depressed and isolated mindset and represented by a subtle camera movement. While we are originally introduced to Travis in this scene as he sets himself up in front of the mirror, the camera quickly becomes the mirror, reflecting Travis exactly how he sees himself as he repeats the same words while confronting his own image: "You talkin' to me?" While at first Travis’s words could be interpreted as being directed at the audience, the mise-en-scène tells a different story entirely. As Travis asks his reflection who he is talking to, the noticeable de-centring of the character as he appears to the right of the screen, not looking ahead but instead to his left, combined with the diegetic sounds of the world outside creates a scene that echoes and questions Travis's psychological state. Furthermore, the hustle and bustle of the outside world reflects the demons that Travis battles as an isolated character with past traumas and his anger at society is represented by the recurring presence of these overwhelming sounds throughout the sequence. The scene in its entirety reflects insanity, as evidenced when Travis repeatedly asks his reflection the same question. This is followed by the repetition of words from his diary, intercut with scenes of him lying down and attempting to sleep. These moments signify a character with little grasp on reality, instead being governed by his thoughts with the same question running through his head. In this way, Travis is not confronting a potential antagonist in the mirror scene but rather himself as his grasp on sanity continues to slip away. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch TAXI DRIVER on mubi.com until 4 July 2017 and join the discussion!

curator's noteThis week, our writers were once again confronted with the task of discussing a film that resides outside the norms of film criticism. The bizarre and at often times difficult to watch LA RUPTURE (Claude Chabrol 1970) creates a hectic, drug-addled experience from start to finish which only increases in confusion as the rules of cinematic editing are loosened throughout its running time. The chaos that ensues will no doubt allow room for an stimulating debate with our writers. HOLY MOTHEREM HOUGHTONLA RUPTURE (Claude Chabrol 1970) sees Hélène (Stéphane Audran) and Charles’ (Jean-Claude Drouot) marriage tested following an argument, culminating in Charles attacking their young son Michel (Laurent Brunschwick) in a violent rage. While Hélène seeks to care for her injured son and save them both from her volatile husband, Charles’ father, Ludovic (Michel Bouquet), goes to extreme lengths to find proof that Hélène is an unfit mother as he attempts to ensure Charles gains custody of his son. There is a lot to be explored in Hélène’s character and her presentation of femininity. She is vulnerable yet courageous; she is strong enough to fight relentlessly for her child, but is able to be emotionally broken just the same as any other person. This duality between courage and vulnerability mirrors the two sides of Hélène the audience is shown. Charles’ parents discover that she was a stripper before she married and it is used as evidence that she is an incompetent mother, even though it was an aspect of her life she chose to put behind her and should not define her identity. This leaves Hélène suspended between two character tropes stereotypically associated with females: the undignified and immoral “whore” and the caring mother. She finds herself in the uncomfortable and unnecessary position of witnessing her past decisions and mistakes manipulate the new life she has chosen for herself and her child. Regardless of her past as a sex worker, Hélène has done nothing wrong. She is presented to the audience as a good-natured and caring mother. However, Charles’ parents continuously criticise and exploit her due to her low social standing and wealth compared to their own. It is this commentary on Hélène’s own femininity that is a truly engaging aspect of LA RUPTURE, as she feels the weight of everyone’s preconceptions about her due to her past as she simply tries to save herself and Michel. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch LA RUPTURE on mubi.com until 5 May 2017 and join the discussion!

curator's noteThis week, our writers were once again confronted with the task of discussing a film that resides outside the norms of film criticism. The bizarre and at often times difficult to watch LA RUPTURE (Claude Chabrol 1970) creates a hectic, drug-addled experience from start to finish which only increases in confusion as the rules of cinematic editing are loosened throughout its running time. The chaos that ensues will no doubt allow room for an stimulating debate with our writers. MENTAL ILLNESS IN LA RUPTURESUMMER MANNINGThe neglect and abuse of mentally ill characters such as Charles and Elise is common in media, with notable examples being WALTER (Stephen Frears 1982) and FORREST GUMP (Robert Zemeckis 1994). A disturbing aspect of LA RUPTURE (Claude Chabrol 1970) is its treatment of mental illness. Charles (Jean-Claude Drouot) is a man struggling with drug addiction and is unable to cope with his illness. Rather than the film following his journey to becoming drug free or learning how to manage his symptoms, the story focuses on how his illness affects those around him. His wife (Stéphane Audran) and father (Michel Bouquet) spend their time blaming each other for his mental state while he is left at home. When he is finally on screen again he tells his wife “It’s as if I’m dead here”, which suggests that he is treated as less than a person, even in his childhood home because of his disability. Another mentally disabled character depicted in LA RUPTURE is Elise (Katia Romanoff), a childlike teenage girl who is taken advantage of. In a harrowing scene (which victims of sexual assault are advised to avoid watching) Paul Thomas (Jean-Pierre Cassel) drugs and kidnaps Elise and takes her to his girlfriend (Catherine Rouvel) who is disguised as Hélène and they force her to watch a pornographic film whilst “Hélène” gropes her. Elise is chosen as a victim because she is vulnerable. She is powerless to stop them whilst under the influence of drugs, and due to her disability is unable to understand the nature of her sexual assault or be able to seek help. When the film was released in 1970 such treatment of those who are mentally disabled was not protested at the time, demonstrating a shift in the reception of mentally ill characters, as the above scene would be a source of contention for modern audiences. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch LA RUPTURE on mubi.com until 5 May 2017 and join the discussion!

curator's noteFor the MUBIVIEWS debut film we wanted to challenge our writers by discussing the sensitive topic of gender exploration, which is so rarely seen from a child’s point-of-view. The film in question is French social realist drama TOMBOY (Céline Sciamma 2011) about a ten-year-old tomboy who passes as a boy to her friends throughout the course of the summer. The unfamiliar setting for the protagonist Laure (Zoé Héran) allows her to safely experiment with her gender through her persona Mickäel. The film tackles isolation, identity and friendship in a tone which MUBI itself describes as ‘delicate and insightful’ highlighting the innocence behind the film. PLAYING THE BOYMATTHEW WEARSTOMBOY (Céline Sciamma 2011) is a film that documents the gender exploration of Laure (Zoé Héran), a ten-year-old girl who adopts the name Mickäel after moving into a new neighbourhood during the summer holidays. The film tackles an issue that has been displayed on our screens in such a dark manner time and time again with films such as the uncompromising realist drama BOYS DON’T CRY (Kimberly Peirce 1999) and more recent romantic biographical drama THE DANISH GIRL (Tom Hooper 2015). TOMBOY instead opts for a more light-hearted, almost consequence-free approach, but offers as poignant a social commentary as any film of its type. The light-heartedness is completely intentional. The question of whether Laure is merely experimenting or whether this is something more is asked throughout the film. The hot, sweaty, summer that never ends backdrop acts as a narrative tool to foreground the idea that this all may just be a phase for Laure. As the summer draws to a close, so does her exploration of gender. It is often difficult to distinguish between what is sexual exploration and what is in fact play. The scene in which Laure's younger sister Jeanne (charmingly played by Malonn Lévana) applies make-up to her older sibling blurs this line even further as we are made aware that Laure’s actions may just be light-hearted childlike behaviour. As Laure’s mother parades her across town in a dress, her acknowledgement “I don’t mind you playing the boy, it doesn’t even make me sad” makes it hard to look at TOMBOY as anything other than a commentary on transgenderism. The film makes links between play and real life, offering an insight into how “playing the boy” as a child is socially acceptable but anything more than this and it becomes a serious, almost punishable offence. TOMBOY is a story that could have easily gone down a melancholy route but it would have lost its real impact. It really is refreshing to see that this is a child who has been nurtured by her family; a child who has not experienced a broken upbringing. This is a film that challenges these narratives approaches and, in doing so, reveals a debate that is really rather unique. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch TOMBOY on mubi.com until 3 April 2017 and join the discussion!

curator's noteFor the MUBIVIEWS debut film we wanted to challenge our writers by discussing the sensitive topic of gender exploration, which is so rarely seen from a child’s point-of-view. The film in question is French social realist drama TOMBOY (Céline Sciamma 2011) about a ten-year-old tomboy who passes as a boy to her friends throughout the course of the summer. The unfamiliar setting for the protagonist Laure (Zoé Héran) allows her to safely experiment with her gender through her persona Mickäel. The film tackles isolation, identity and friendship in a tone which MUBI itself describes as ‘delicate and insightful’ highlighting the innocence behind the film. À LA MODE OR "IN THE FASHION"?SUMMER MANNINGA standout moment of TOMBOY (Céline Sciamma 2011) involves Laure (Zoé Héran) altering a red one-piece bathing suit to go swimming with new friends and pass as a boy. When she tries on her makeshift briefs, she realises that her body will not look like the other boys’. Her resourceful solution to use PlayDoh to create a packer (an item worn in one’s underwear to create the illusion of a penis) highlights her childish innocence - using a child’s toy designed for fun and creativity - but also her self-awareness. While it is suggested throughout the film that gender fluidity is merely a phase of childhood, the decision to later store away the packer suggests otherwise. Laure places it in a box with her baby teeth for safekeeping, as if it is precious and needs protecting, suggesting that she may use it again. The loss of her baby teeth connotes the beginning of a loss of her innocence and a childish androgyny as she begins to grow into an adult body. The packer is a tangible symbol of her persona as a boy which she keeps hidden from her family in order to keep her experimentation a secret. When she learns of her apparent lies, Laure’s mother (Sophie Cattani) forces her to wear a blue frilly dress and visit the other children to apologise for lying. This acts as a metaphorical confinement of her gender; everyone around her is forced to see her as female and understand that she was passing as a gender which she does not know if she belongs to or not any more. There is a quiet power in her later removing the dress in an act of defiance against the expectations put upon her. It is a rejection of gender norms rarely displayed in child characters yet is representative of many children exploring and learning about their own identities. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch TOMBOY on mubi.com until 3 April 2017 and join the discussion!

curator's noteFor the MUBIVIEWS debut film we wanted to challenge our writers by discussing the sensitive topic of gender exploration, which is so rarely seen from a child’s point-of-view. The film in question is French social realist drama TOMBOY (Céline Sciamma 2011) about a ten-year-old tomboy who passes as a boy to her friends throughout the course of the summer. The unfamiliar setting for the protagonist Laure (Zoé Héran) allows her to safely experiment with her gender through her persona Mickäel. The film tackles isolation, identity and friendship in a tone which MUBI itself describes as ‘delicate and insightful’ highlighting the innocence behind the film. WHAT IS A TOMBOY?EM HOUGHTONWhile the word “tomboy” in English is still shrouded in stigma of gender non-conformity, the French definition “garçon manqué” - which translates literally as “failed boy” - lends a more powerful look at what gender means for ten-year-old Laure (Zoé Héran) in the French coming-of-age drama TOMBOY (Céline Sciamma 2011). Laure’s gender is left unstated until a delicate moment when her female genitalia is revealed as she steps naked from the bath. This moment not only establishes that Laure is biologically female, it also shows how involuntary her gender is. Only when she is stripped bare of the male physicality she has tried so hard to perfect is it clear that she is not who she wants to be. Laure spends a lot of time learning to act like a boy, creating a fake PlayDoh penis to position in the swimming trunks she has fashioned herself out of a girl's swimsuit, as well as spitting like her male friends when they play football. She goes to these extremes to mask her femininity in order to create a character to whom she can relate: Mickäel. The film’s title replicates the same sense of vagueness that is felt by Laure in her gender identity as the “garçon manqué”. TOMBOY symbolises the struggle of young girls who do not want to conform to society’s gender roles and Laure does so by adopting a male way of life. Because of this, the film serves as a powerful commentary on the representation of gender as something that is much more than biology. While Laure is biologically female, she creates a male façade that she uses to become more comfortable in her own skin. The persona of Mickäel creates a sense of safety for Laure as she leaves behind the expectations of her femininity. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch TOMBOY on mubi.com until 3 April 2017 and join the discussion!

|

MUBIVIEWSOne MUBI film, five perspectives, endless possibilities. Archives

July 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed