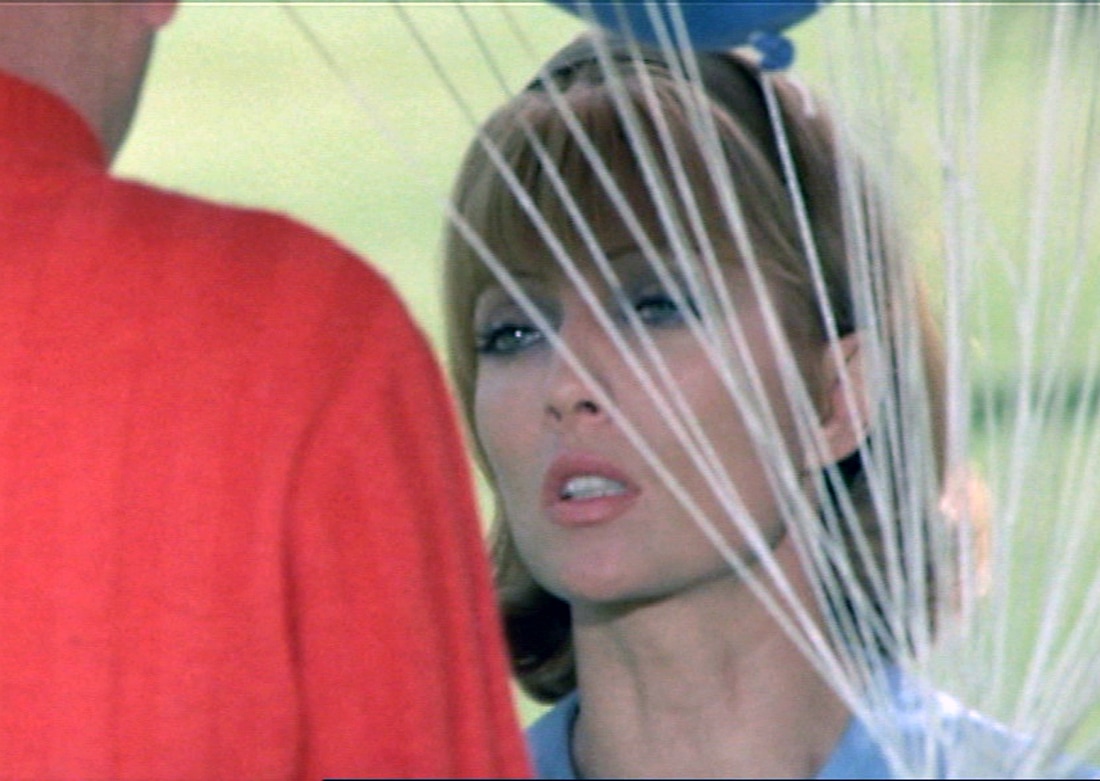

curator's noteThis week, our writers were once again confronted with the task of discussing a film that resides outside the norms of film criticism. The bizarre and at often times difficult to watch LA RUPTURE (Claude Chabrol 1970) creates a hectic, drug-addled experience from start to finish which only increases in confusion as the rules of cinematic editing are loosened throughout its running time. The chaos that ensues will no doubt allow room for an stimulating debate with our writers. BELIEVING BUT NOT SEEINGGEORGE LEEThe theme of perception is quickly established in LA RUPTURE with Charles’ (Jean-Claude Drouot) parents trying to paint Hélène (Stéphane Audran), their daughter-in-law, in a negative light. Their ultimate goal by doing this is to gain custody of their grandson in the proceeding divorce trial. The assumed reason for their negative perception of Hélène is their belief that she is sexually promiscuous. This belief is presented when Helene was revealed to once have been a stripper, but as she describes it: “That didn’t last long”. Helene thinks Charles is a helpful and honest man simply because he is handsome and charming and Charles thinks that the young girl with mental difficulties will be able to be fooled by a simple wig. All these perceptions turn out to be false, leading to the characters varying downfalls with Hélène being betrayed and Charles’ true nature being revealed. LA RUPTURE is undeniably a critique of the bourgeois by painting the rich as evil and manipulative but the way this particular film handles this is to comment on the controlling class’s understanding of perception. What the rich believe as true must be so as they are the ones in power and have the most influence. It is up to Hélène - the representation of the working class - to call them out on their lies. The film was released on the tail end of the French New Wave when perceptions on cinema were changing. The film, therefore, takes a difference route of expression. By the third act, the film diverts away from logical narrative and leans towards surrealism. With the main characters drugged, we are witness to a dream-like sequence from Hélène’s point-of-view. It may not make much sense in contrast to films today but this is the point. We are forced to throw away our existing perceptions of the film and attempt to decide significant elements for ourselves. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch LA RUPTURE on mubi.com until 5 May 2017 and join the discussion!

0 Comments

curator's noteThis week, our writers were once again confronted with the task of discussing a film that resides outside the norms of film criticism. The bizarre and at often times difficult to watch LA RUPTURE (Claude Chabrol 1970) creates a hectic, drug-addled experience from start to finish which only increases in confusion as the rules of cinematic editing are loosened throughout its running time. The chaos that ensues will no doubt allow room for an stimulating debate with our writers. A CLASS OF THEIR OWNMATTHEW WEARSConsidered a master in the mystery genre, Claude Chabrol interwove themes of class struggle and injustice into many films in his catalogue during his golden era. His 1970 experimental melodrama, LA RUPTURE, is certainly no exception to this. The film examines class warfare in an often uncompromising fashion, with the absurdities of the film being an exaggerated social reflection of the class system in France at the time. Mirroring the increased socialist movements within this period, the film is a severe critique on the astonishing power and destructive nature of wealth. Focusing on the custody battle between Hélène Régnier (Stéphane Audran) and her mentally ill husband Charles (Jean-Claude Drouot) over their young son Michel (Laurent Brunschwick), the film offers a strong commentary about the relationship between power and wealth. Money is viewed as a weapon whereby any character that possesses a greater amount is far more capable of obtaining their desire, even to the degree of taking a child from its own mother when it is unwarranted. At no point should the custody of the child be put into question as Hélène is clearly the more competent of the parents. Charles has physically abused both Hélène and Michel, however still stands a chance at being the carer of his child simply because of his rich parents. The film is effective in showcasing the full extent of the power of wealth as the bourgeoisie family are able to use their affluence as a controlling device in order to manipulate Hélène from behind a veil, without her having any knowledge of them doing so. Their money has tainted them and they have lost the virtues that the working class Hélène possesses: integrity, kindness and love. LA RUPTURE is a film that at times can appear quite ludicrous. There are moments where it can be difficult to believe just how far Charles' parents will go in order to gain custody of Michel, often reaching levels whereby they bypass their greedy higher class representations and become nothing short of evil. This film is not just a commentary of the privileged, but rather an outright attack on their morals and ethics. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch LA RUPTURE on mubi.com until 5 May 2017 and join the discussion!

curator's noteThis week, our writers were once again confronted with the task of discussing a film that resides outside the norms of film criticism. The bizarre and at often times difficult to watch LA RUPTURE (Claude Chabrol 1970) creates a hectic, drug-addled experience from start to finish which only increases in confusion as the rules of cinematic editing are loosened throughout its running time. The chaos that ensues will no doubt allow room for an stimulating debate with our writers. HOLY MOTHEREM HOUGHTONLA RUPTURE (Claude Chabrol 1970) sees Hélène (Stéphane Audran) and Charles’ (Jean-Claude Drouot) marriage tested following an argument, culminating in Charles attacking their young son Michel (Laurent Brunschwick) in a violent rage. While Hélène seeks to care for her injured son and save them both from her volatile husband, Charles’ father, Ludovic (Michel Bouquet), goes to extreme lengths to find proof that Hélène is an unfit mother as he attempts to ensure Charles gains custody of his son. There is a lot to be explored in Hélène’s character and her presentation of femininity. She is vulnerable yet courageous; she is strong enough to fight relentlessly for her child, but is able to be emotionally broken just the same as any other person. This duality between courage and vulnerability mirrors the two sides of Hélène the audience is shown. Charles’ parents discover that she was a stripper before she married and it is used as evidence that she is an incompetent mother, even though it was an aspect of her life she chose to put behind her and should not define her identity. This leaves Hélène suspended between two character tropes stereotypically associated with females: the undignified and immoral “whore” and the caring mother. She finds herself in the uncomfortable and unnecessary position of witnessing her past decisions and mistakes manipulate the new life she has chosen for herself and her child. Regardless of her past as a sex worker, Hélène has done nothing wrong. She is presented to the audience as a good-natured and caring mother. However, Charles’ parents continuously criticise and exploit her due to her low social standing and wealth compared to their own. It is this commentary on Hélène’s own femininity that is a truly engaging aspect of LA RUPTURE, as she feels the weight of everyone’s preconceptions about her due to her past as she simply tries to save herself and Michel. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch LA RUPTURE on mubi.com until 5 May 2017 and join the discussion!

curator's noteThis week, our writers were once again confronted with the task of discussing a film that resides outside the norms of film criticism. The bizarre and at often times difficult to watch LA RUPTURE (Claude Chabrol 1970) creates a hectic, drug-addled experience from start to finish which only increases in confusion as the rules of cinematic editing are loosened throughout its running time. The chaos that ensues will no doubt allow room for an stimulating debate with our writers. MENTAL ILLNESS IN LA RUPTURESUMMER MANNINGThe neglect and abuse of mentally ill characters such as Charles and Elise is common in media, with notable examples being WALTER (Stephen Frears 1982) and FORREST GUMP (Robert Zemeckis 1994). A disturbing aspect of LA RUPTURE (Claude Chabrol 1970) is its treatment of mental illness. Charles (Jean-Claude Drouot) is a man struggling with drug addiction and is unable to cope with his illness. Rather than the film following his journey to becoming drug free or learning how to manage his symptoms, the story focuses on how his illness affects those around him. His wife (Stéphane Audran) and father (Michel Bouquet) spend their time blaming each other for his mental state while he is left at home. When he is finally on screen again he tells his wife “It’s as if I’m dead here”, which suggests that he is treated as less than a person, even in his childhood home because of his disability. Another mentally disabled character depicted in LA RUPTURE is Elise (Katia Romanoff), a childlike teenage girl who is taken advantage of. In a harrowing scene (which victims of sexual assault are advised to avoid watching) Paul Thomas (Jean-Pierre Cassel) drugs and kidnaps Elise and takes her to his girlfriend (Catherine Rouvel) who is disguised as Hélène and they force her to watch a pornographic film whilst “Hélène” gropes her. Elise is chosen as a victim because she is vulnerable. She is powerless to stop them whilst under the influence of drugs, and due to her disability is unable to understand the nature of her sexual assault or be able to seek help. When the film was released in 1970 such treatment of those who are mentally disabled was not protested at the time, demonstrating a shift in the reception of mentally ill characters, as the above scene would be a source of contention for modern audiences. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch LA RUPTURE on mubi.com until 5 May 2017 and join the discussion!

curator's noteThis week, our writers were once again confronted with the task of discussing a film that resides outside the norms of film criticism. The bizarre and at often times difficult to watch LA RUPTURE (Claude Chabrol 1970) creates a hectic, drug-addled experience from start to finish which only increases in confusion as the rules of cinematic editing are loosened throughout its running time. The chaos that ensues will no doubt allow room for an stimulating debate with our writers. RUPTURING THE SENSESSTEVEN FEGANLA RUPTURE (Claude Chabrol 1970) begins with a rattle of the senses, living up to its namesake as it subverts the conventions of a slow-burn set-up to the story and instead introduces two of its primary characters in a spectacularly sudden incident. However, before this, the film opens with the foreboding words: “What utter darkness suddenly surrounds me?” spoken by French dramatist Jean Racine who was known for combining elements of comedy and tragedy. These words have instant connotations of unexpectedness and subversion from conventional modes of storytelling as the opening scene plays out and, in hindsight, acts as a warning for the viewer. They also attest to the overall theme of surprise and suspense throughout the film where there is rarely any warning or exposition as to the fate of these characters. We are introduced to our main protagonist Hélène (Stéphane Audran), as she prepares her son’s breakfast. Her husband Charles (Jean-Claude Drouot) stumbles out from another room and without warning or incitement, assaults his wife and subsequently their son (Laurent Brunschwick). This startling event, both for Hélène and the audience, immediately fractures the subtle introduction previously set up to provide an unpredictable series of events that later unfold. The tenacious start to the film immediately poses several questions to the spectator as there is no explanation for Charles’ actions. But before the audience can even begin to speculate the reasons for his sudden burst of violence against his wife, he lifts his son into the air and throws him against a nearby table. At this point, the film surpasses questions of domestic abuse and instead invites the audience to question the unpredictable direction of the film itself. LA RUPTURE sets out to do exactly what its title suggests: rupture the conventions of story set-up and defy the expectations of its audience to provide a fresh and unexpected thriller that never truly explains itself, a trademark style that Chabrol utilised throughout his career. In doing so, it maintains the suddenness and confusion that a breach of any kind usually presents. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch LA RUPTURE on mubi.com until 5 May 2017 and join the discussion!

|

MUBIVIEWSOne MUBI film, five perspectives, endless possibilities. Archives

July 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed