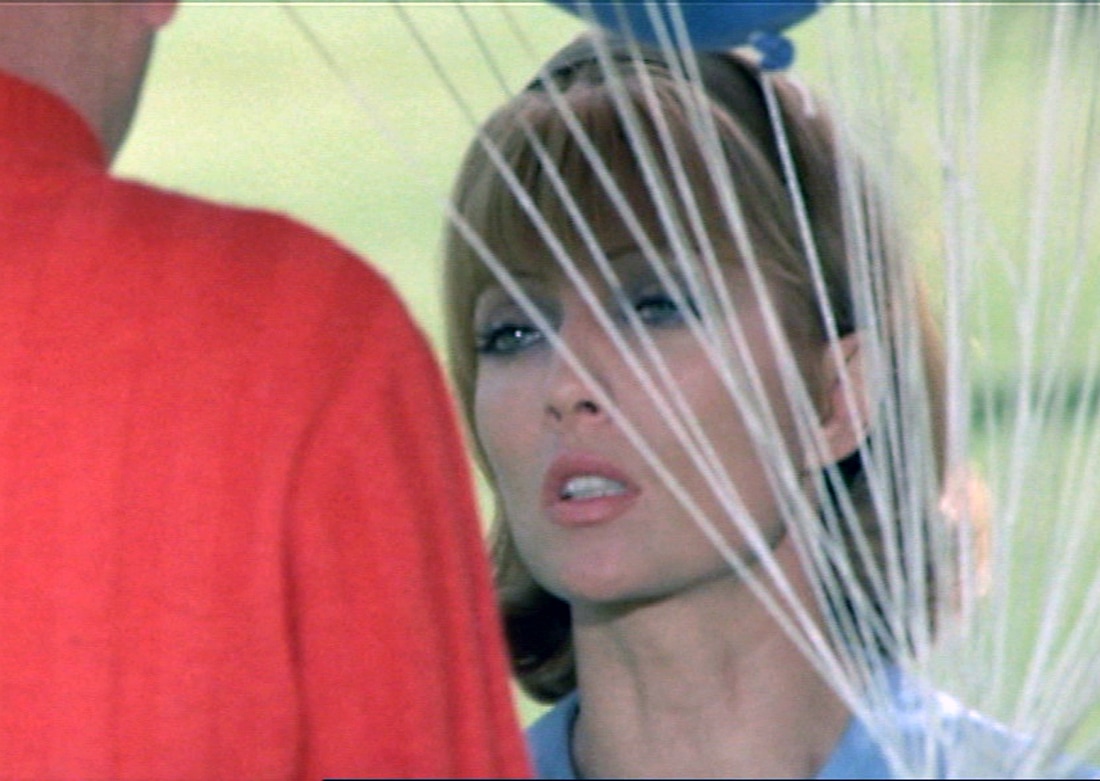

curator's noteThis week, our writers were once again confronted with the task of discussing a film that resides outside the norms of film criticism. The bizarre and at often times difficult to watch LA RUPTURE (Claude Chabrol 1970) creates a hectic, drug-addled experience from start to finish which only increases in confusion as the rules of cinematic editing are loosened throughout its running time. The chaos that ensues will no doubt allow room for an stimulating debate with our writers. BELIEVING BUT NOT SEEINGGEORGE LEEThe theme of perception is quickly established in LA RUPTURE with Charles’ (Jean-Claude Drouot) parents trying to paint Hélène (Stéphane Audran), their daughter-in-law, in a negative light. Their ultimate goal by doing this is to gain custody of their grandson in the proceeding divorce trial. The assumed reason for their negative perception of Hélène is their belief that she is sexually promiscuous. This belief is presented when Helene was revealed to once have been a stripper, but as she describes it: “That didn’t last long”. Helene thinks Charles is a helpful and honest man simply because he is handsome and charming and Charles thinks that the young girl with mental difficulties will be able to be fooled by a simple wig. All these perceptions turn out to be false, leading to the characters varying downfalls with Hélène being betrayed and Charles’ true nature being revealed. LA RUPTURE is undeniably a critique of the bourgeois by painting the rich as evil and manipulative but the way this particular film handles this is to comment on the controlling class’s understanding of perception. What the rich believe as true must be so as they are the ones in power and have the most influence. It is up to Hélène - the representation of the working class - to call them out on their lies. The film was released on the tail end of the French New Wave when perceptions on cinema were changing. The film, therefore, takes a difference route of expression. By the third act, the film diverts away from logical narrative and leans towards surrealism. With the main characters drugged, we are witness to a dream-like sequence from Hélène’s point-of-view. It may not make much sense in contrast to films today but this is the point. We are forced to throw away our existing perceptions of the film and attempt to decide significant elements for ourselves. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch LA RUPTURE on mubi.com until 5 May 2017 and join the discussion!

0 Comments

curator's noteFor the MUBIVIEWS debut film we wanted to challenge our writers by discussing the sensitive topic of gender exploration, which is so rarely seen from a child’s point-of-view. The film in question is French social realist drama TOMBOY (Céline Sciamma 2011) about a ten-year-old tomboy who passes as a boy to her friends throughout the course of the summer. The unfamiliar setting for the protagonist Laure (Zoé Héran) allows her to safely experiment with her gender through her persona Mickäel. The film tackles isolation, identity and friendship in a tone which MUBI itself describes as ‘delicate and insightful’ highlighting the innocence behind the film. REALISING THE ISSUESGEORGE LEESocial realism is a film genre which brings to the forefront members of society that are often underrepresented. TOMBOY (Céline Sciamma 2011) uses social realist techniques to tell a story of the exceptional nature of the everyday. From its use of handheld cameras to the contemporary setting, the film remains within the boundaries of realism. Social realism often comes hand in hand with a strong political message that the filmmaker feels must be brought to attention and, in the case of TOMBOY, it is the politics of experimenting with gender and sexuality through the perspective of a ten-year-old. Social realism often avoids the use of a mainstream narrative structure. This is very apparent in TOMBOY where the film does not have a succinct ending; it feels as though it never leaves the second act. This can be seen as a metaphor for the experience of transgender children where they feel something is disjointed about their lives. A significant line is where Laure’s mother asks her: “Got an idea? Cos if you do, please say so, I can’t think of any. Have you got a solution?”. This is a shocking statement because it reveals that there is a lack of support system in place if Laure decided that she does in fact identify as a boy. Even if there was, it is questionable that a ten-year-old would be aware of the level of support in place for people that are transgender. The use of handheld camera positions us in relation to Laure’s childlike point-of-view so her confusion is that much more impactful. The point the film is trying to make is that these issues need to be discussed from a young age to increases awareness and subsequently highlight the issue in society. The use of social realism as a storytelling technique really cements this and makes the film less of an entertainment piece but an honest critique of our current societal position. Every day this week a different writer will provide their perspective on our MUBIVIEWS film and each post will be open to comments from our readers. Watch TOMBOY on mubi.com until 3 April 2017 and join the discussion!

|

MUBIVIEWSOne MUBI film, five perspectives, endless possibilities. Archives

July 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed