A REALISTIC ROMANCE

|

With his auteur style firmly at the helm, Woody Allen’s MANHATTAN (1979) provides its audience with a unique take on the romantic comedy genre, moving away from the traditional boy-meets-girl trajectory that culminates with a happily-ever-after kiss. This deviation from the stereotypical narrative is unmistakably connected to Woody Allen whose earlier iconic films ANNIE HALL (1977) and INTERIORS (1978) are clearly inspired by 1930s screwball comedies. What materialises from this is a no longer clear cut narrative and when the final credits on MANHATTAN roll, we are left with the question: is there a happy ending?

The black and white aesthetic of MANHATTAN’s opening scene provides a beautiful and romanticised view of Manhattan, which is only further enhanced with George Gershwin’s musical accompaniment, bringing vibrancy to the monochrome colour palette. In an opening monologue, protagonist Isaac (Allen) professes his love for the city numerous times when working on the first chapter of his book. Although Isaac reverently states his adoration for the grand city, the rest of his relationships are not nearly as straightforward. All of the relationships seen through the course of the narrative are fragmented in one way or another, presenting us with a realistic if somewhat pessimistic view of love within a contemporary society. Taking the debate of monogamy (that becomes an overarching theme of the film), Isaac’s 17-year-old girlfriend Tracy (Mariel Hemmingway) questions whether people are supposed to spend their life with just one person or whether they should have multiple lovers. This discussion is reinforced with the marriage of Yale (Michael Murphy) and Emily (Anne Byrne). Yale partakes in numerous extramarital affairs. After their breakup, Emily tells Isaac that she knew about his adultery and accepted it as “marriage requires some compromise”. Her belief is that marriage is an outdated ritual in modern culture. During the final scenes of the film, Isaac argues a need for people to retain their personal integrity so that when future generations look back they will be seen as good people. However, it is Yale who provides the most honest remark stating that “we are only human beings” and with that comes a high level of mistakes and imperfection. Although all the characters strive for perfection within their relationships, they ultimately find that no matter how much you romanticise it, love is as disordered as the streets of New York and happy endings are ambiguous delusions. |

NEW AND NEUROTIC: REDEFINING THE LEADING MAN

|

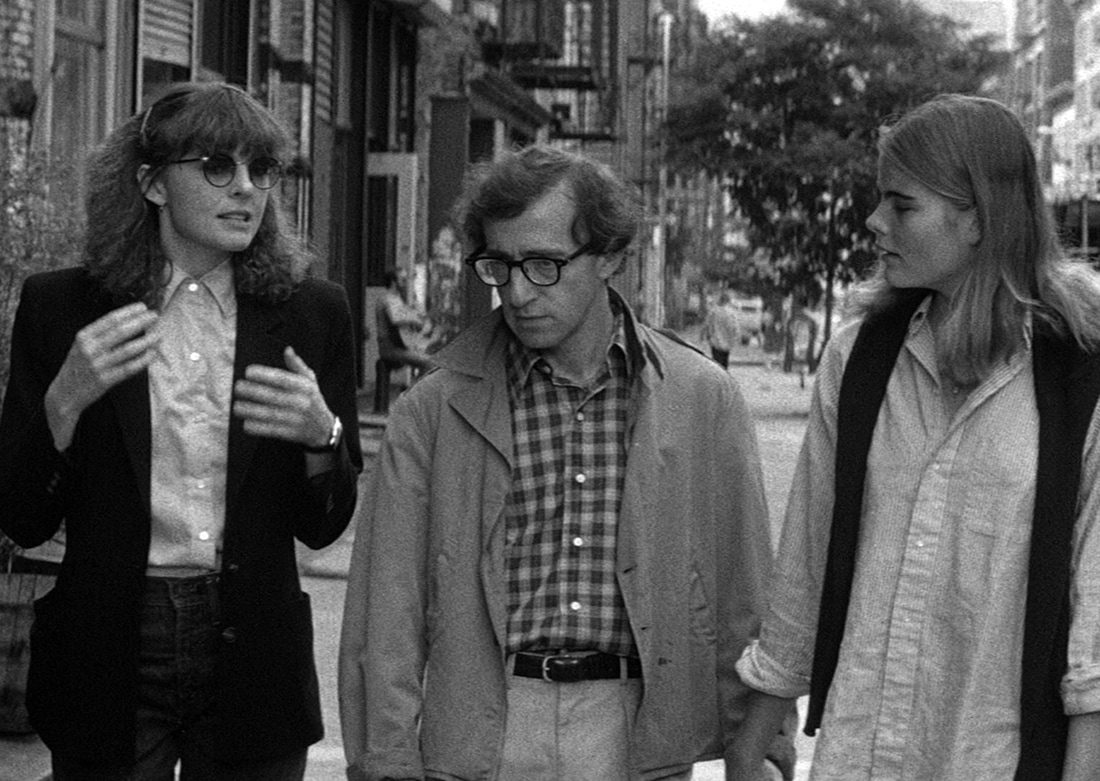

As MANHATTAN (Woody Allen 1979) opens, we are granted with stunning views of the Manhattan skyline, the bustling streets beneath and a wavering jazz melody. This is soon undercut by the nasal tones of Woody Allen’s Isaac as he meanders around the introduction to his new book. While Allen is widely acknowledged for redefining the romantic comedy genre, in doing so he also redefined the idea of the leading man. If it were not for Allen’s character’s in ANNIE HALL (Woody Allen 1977) and MANHATTAN then there would be no Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s misplaced romantic Tom from (500) DAYS OF SUMMER (Marc Webb 2009) nor Steve Carell’s myriad of awkward singletons from THE 40-YEAR-OLD VIRGIN (Judd Apatow 2005) or CRAZY, STUPID, LOVE (Glenn Ficarra and John Requa 2011). Allen paved the way for these bumbling and whining characters by not following in the footsteps of the romantic comedies before him but by creating characters brimming with neuroses and narcissism.

Allen takes a lot of cues from European filmmakers before him such as Fellini and Godard by externalising his characters’ existential angst. Allen does away with the classical plot driven structure, instead focusing on the individual problems of his characters. These problems, however, are all of their own doing and they make decisions that are bound to backfire. Isaac quits his perfectly good job on a whim and Mary (Diane Keaton), Isaac’s current love interest, goes on a double date opposite her adulterous ex-boyfriend and his wife. While ultimately driving the plot forward, the problems are created as a distraction for these deeply unsettled characters. Allen’s characters all have a variety of issues that leads them to turn to “psychoanalytic” treatment. This is where Allen’s romantic comedy really differs from earlier, more traditional, examples of the genre where problems are designed to be solved before the credits roll. Allen’s character, however, experiences more deep-seated issues that are reflective of real life. Isaac is so neurotic and filled with self-doubt that he constantly overcompensates to the point that he might be considered narcissistic. Nearly every other sentence is some kind of self-compliment intent on reassuring his faltering ego. This need for validation is what takes us to the climax of the film. With Mary gone, Isaac realises that he should have stayed with his 17-year-old girlfriend, seemingly for the sole purpose that she loved him unconditionally. This is not a tale of true love but one man’s search for validation through romance. Isaac is not the macho man of romantic films of the past – he is whiny and not to be admired – but that is why the film is so compelling. It is clear to see that Allen’s departure from the norm secured his influence on not only the romance films that followed but on the broader medium of cinema. |

CONDESCENDING CULTURE

|

Set in a forward-thinking city full to the brim with artists and writers, it should come as no surprise that MANHATTAN (Woody Allen 1979) has an undeniable air of pretentiousness. Whether brief glances of the Guggenheim or long debates about the merit of simplistic steel sculptures, Woody Allen’s romantic comedy reminds us time and time again that we are culturally inferior to the characters on screen. With seemingly never-ending connections to the arts and media, Isaac’s (Allen) circle of friends and ex-lovers are all authors, artists or ingénues who are expertly informed about early French cinema and Diane Arbus-inspired photography in ways we could only dream of.

The unbelievable cultural climate constructed by MANHATTAN borders on unbearable at times such as when cynical writer Mary (Diane Keaton) denouncing the likes of Ingmar Bergman and F. Scott Fitzgerald by categorising them into her “academy of the overrated”. While this could be seen as an empowering refusal to acknowledge the hegemonic art canon, Mary does not provide alternatives for Bergman or Fitzgerald and instead uses her time to simply suggest how inferior and overrated they are in comparison to her views regarding the art world. This parallels how Isaac is described in his ex-wife’s memoir, stating that “He had complaints about life but never any solutions”. For Isaac and his cohort, their privileged Manhattan artist lives provide little trouble, so they must make their own through formulated drama such as extra-marital affairs or by dating underage, inexperienced girls. Although it is clear that these caricatures of middle-class New York are a form of satire, the frustration of hearing their pseudo-intellectual drivel is inescapable. When we first meet Mary, she is abrasive and immediately shoots down Isaac’s personal taste in art at the Guggenheim, presenting an ostentatious insight into what the real highlights of the collection are. In this moment we side with Isaac but, as the film progresses, we see how equally egocentric he is towards his own writing, quitting his highly successful and praised job in the television industry to write a book about his life. No doubt this parallels Allen’s experiences or beliefs of how the upper echelons of New York’s art circle run, but the film fails to provide us with an alternative. The self-aggrandising world of MANHATTAN becomes draining. It should therefore come as no surprise that the film was inspired by Allen’s love of George Gershwin’s music, ultimately imbuing the entire film with cultural references with an equally high caliber of pomp. |

MANHATTAN screened on Tuesday 13 June at the Southampton Showcase Cinema de Lux as a special screening hosted by Park Circus. Allen's monochrome masterpiece was the first of the director's classic oeuvre to be made available digitally by Park Circus having received its UK premiere at the BFI London Film Festival 2016. Showcase/Park Circus special screenings run until 15 June.