|

|

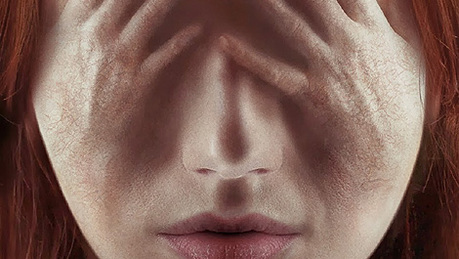

Perhaps the most ingenious trick of Mike Flanagan’s chilling horror is that nothing on the surface is quite what it seems. Based on Flanagan’s earlier short film Oculus: Chapter 3 – The Man with the Plan (2006), the psychological horror avoids the mistakes of becoming yet another symptomatic and mediocre horror. After his incarceration and time spent in therapy for murdering his father, Tim (Brenton Thwaites) is reacquainted with his sister Kaylie Russell (Karen Gillan). Convinced an antique mirror is responsible for a series of murders, the superstitious siblings revisit the crime scene of their childhood to prove their father’s death was at the hands of paranormal phenomena.

The often-unpredictable narrative bends as two plots unravel at the Russell’s family house at different points in time. The present day Russell kids, often engaging in comical sibling banter, are out to ghost-bust the paranormal with an elaborate arsenal of cameras, heat detectors and clocks. As their tale unspools, the scenes are intercut with flashbacks of their childhood selves encountering the supposedly supernatural mirror for the first time. Flanagan’s film constructs an eerie and thickening uncertainty as the film’s narrative becomes hallucinatory and layered in tensions between the rational and the irrational. At one revelatory moment, Kaylie recites the long-winded and bloodied history of the mirror’s ownership, noting the several gruesome deaths in its backstory and the sceptical Tim responds by asserting the importance of “correlation and causation”. This reveals Flanagan’s sleight of hand in the film’s manipulative editing and the bending plot that incites as much as it frightens as the film cuts between time and space to separate the rational from the irrational. The shrewd direction administers a dose of suspense and the suspended disbelief in the “real” evokes Steven Soderbergh’s otherworldly purgatory Solaris (2002). Flanagan’s modest horror is about family drama and, after some clumsy visual and aural foreplay, it climaxes in a few moments of genuine terror and fright. Composed by the Newton Brothers, the soundscape is heavy and haunting with the infrequent chirping of high-pitched alarm clocks and cell-phone ringtones to create a disarraying atmosphere. The film also displays technical skill and the scares are framed to make an impact as things creep and crawl at the fringes of the screen. When the indifferent Kaylie stares into the mirror at a warehouse of antiques, three cloaked statuettes (eerily similar to Doctor Who’s Weeping Angels) are visible in the corner of the mirror. Yet in the room there are only two. For all its playful and puzzling deceitfulness, the odd restraint in withholding scares creates a thrill of the unknown. Oculus is both mentally and physically brutal in its depictions of unravelling psyches. In one unsettling blunder, adult Kylie mistakes a light bulb for an apple, which results in her plucking bloodied shards of glass from her mouth. The novelty of Oculus is watching these characters navigate the sinister labyrinth of their childhood house where chills are tucked away behind corners and strange noises are heard behind closed doors. Surfaces can be deceiving and the mirror’s function in Oculus is to communicate the moral of the story: not everything on the surface is what it appears. Less a clichéd horror trope, the mirror reflects the absurdity of the genre by reliving bizarre circumstances and insinuating a paranormal presence is responsible rather than anything explained via correlation or causation. Oculus does feel familiar. The tense setting of the rickety family house recalls Halloween (1978) while the weird uniformity of the suburban family unit and the shared sweetness of its child characters evokes Poltergeist (1982). Despite these similarities to other films even within the same genre, Oculus is accessible through its modern themes and scenarios. Sheer brutality is manifested in the tragic tale of everyday domestic violence that hides in plain sight. The most moving image sees the battered mother Marie Russell (Katee Sackoff) bolted to the wall and beaten by her husband. This is the real horror of Oculus and, despite the surfaced ruse of the appearing-to-be ordinary family, the post-traumatic outcome weighs heavy on the Russell kids in the modern day. The characters are also victims; the past haunts the Russell children and is what makes them seem so disturbed. Oculus taps into childhood fears and frightening personal experiences and questions adolescence as a time for finding new spooks and thrills. The moral ambiguity of the film is unsettling; the irresponsible and not-so-innocent modern day Russells are always evading reality and trying to conjure some irrational conspiracy. Tim has lost his grip on reality. Recalling the sun-smeared confessions of the delusional Isla Vista killer Elliot Rodger, he is a figure all-to-familiar in the media. The film suggests that the uncertainty of the everyday is something altogether worth fearing and it continuously revisits the line between right and wrong. Flanagan’s shrewd and subtle horror is both steeped in mysticism and ghoulish frights and is a worthy midnight movie that will leave audiences squirming in anticipation and dread. The narrative is refreshing and sophisticatedly structured and the film’s technical skill compliments the brutality and sheer terror of certain panic-induced moments. There are those things that go bump in the night but Oculus presents something much more frightening. |