|

Dreams of interstellar exploration have consistently captured the imaginations of children and great thinkers alike. Whether it is the final frontier, the great beyond, or just the conceptual thought of a perpetual ever-expanding timeless void holding billions upon billions of planets, stars and solar systems have intrigued and inspired academics and astronomers into trying to unlock the secrets of our universe. But modern science can only take us so far in our current exploration of space, so we look to science fiction to play out our other-worldly fantasies.

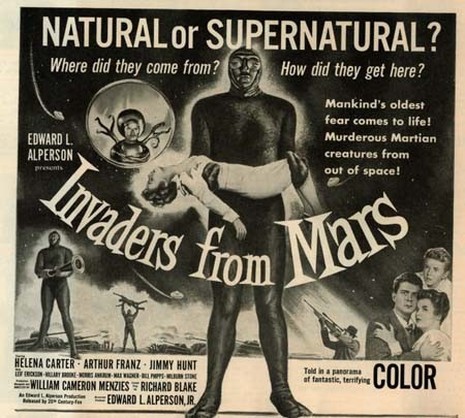

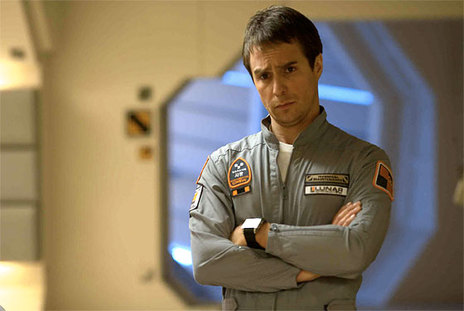

Television and film series such as Star Trek take us on journeys across galaxies to different planets and generate enthusiasm and excitement in their space travel adventure. Science fiction films have historically played on contemporary cultural fears. During the so-called “golden age of science fiction” science fiction films like It Came from Outer Space (1953) and Invaders from Mars (1953) used the idea of extra-terrestrials invading suburban America and disguising themselves as everyday citizens to perpetuate fears of a Russian invasion and the use of Soviet spies during the Cold War. This is not the first time sci-fi and horror have been used to manipulate and reflect cultural anxieties. During World War Two, films like Black Dragons (1942), a film based on a Nazi plastic surgeon who disguises Japanese agents to look like American industrialists, followed the same formula used by the alien invasion films of the 1950s to gain support for potential involvement in conflict against a foreign force. So where does this leave the modern day sci-fi film? Over the last decade the most popular films of the sci-fi genre have been those focused on astronauts exploring space, ranging from the inspirational tale of perseverance in Ron Howard's Apollo 13 (1995) to Duncan Jones’s thought-provoking Moon (2009). Since the early fifties astronauts were the closest a person could get to become a superhero in American culture. They were an elite specialised group who could do what no other man could and carried with them the weight of American history and expectation on every journey. It is clear that the ideology and representation of the astronaut is key to understanding the popularity and socio-cultural importance of these films and is worth exploring in more detail. Apollo 13: Space Travel in Post-Cold War America During a seemingly routine flight, three astronauts (played by Tom Hanks, Kevin Bacon and Bill Paxton) find themselves in grave danger as they attempt to return to Earth when a series of malfunctions leaves their spacecraft in critical condition. Based on a true story, the film’s main focus is the portrayal of the astronauts as everyday people with everyday commitments to friends and family. White, middle class and following the Judeo-Christian ethic, they are the quintessential representation of the American Dream. During the flight the astronauts are faced with one of the fundamental fears of space travel: the unreliability of the spacecraft they are travelling in. With the sheer volume of technical equipment on board there is always a possibility of something malfunctioning, even a component on the smallest scale can jeopardise an entire mission, leaving no room for error. Thrown into this life-threatening situation, our American heroes laugh in in the face of adversity, and by using their own intuition and resilience they overcome the obstacles in their path, returning safely back to Earth. Alongside the US Marine, the American astronaut has been a symbol of national pride in American culture ever since the infamous Space Race with the Soviets (1955-1972). The representation of the three astronauts is no exception; many see Apollo 13 as a symbolic tale of America overcoming any resistance or complication in its journey for the freedom, prosperity and safety of its citizens. The three pilots were in a direct conflict, in battle if you will, with the unknown forces of space but emerged victorious. Moon: The Fear of the Unknown Astronaut Sam Bell (Sam Rockwell) works alone on the Moon, sending vital resources back to Earth in order to combat the diminishing supply of fossil fuels. His only companion is his computer GERTY, programmed to replicate human emotions and conversations. GERTY is crucial to Sam’s survival and mental wellbeing during his three-year contract at the space station as GERTY’s only duty is to look after and help Sam under any circumstance. Moon plays heavily on earlier sci-fi films. GERTY shares an uncanny resemblance to HAL 9000 from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), for example. Moon also shares its cinematic style with 2001; extended sequences of Sam travelling across the Moon's lunar surface and the interior of the space station are clear homages to Kubrick’s sci-fi classic. Like Apollo 13, Sam is portrayed as an everyday, family man with a wife and child he is desperate to return to. At the film’s beginning the audience see Sam as a normal person; he has feelings and emotions like anyone else. But by the end of the film the audience is faced with far more questions than at its outset. In this sense Moon is a metaphor for the potential consequences of intergalactic space travel: who knows what mankind may find or discover? The fear of the unknown is perhaps the greatest fear of all. Moon brilliantly communicates this and the idea that a voyage into space may substantially change the way we view our existence, resultantly meaning that humanity might not be ready for what it uncovers. The Nolan Treatment These two films exhibit the cultural importance of the figure of the astronaut, exploring how a single person can represent the subconscious fears of an entire race and how a group of heroes can portray the values and philosophies of a global superpower in a single mission. With the release of Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar (2014), the symbolic image of the astronaut will continue to be challenged whilst receiving a Nolan makeover, taking the cinematic icon of the astronaut and applying Nolan’s unique use of time, space and visual effects to take us into his vision of humanity’s future beyond the stars. |