|

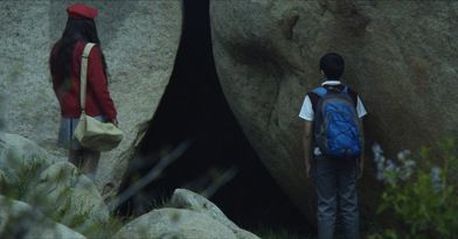

Here Comes the Devil is a dark and twisted tale in which Adolfo (Alan Martinez) and Sara (Michele Garcia), the children of Sol (Laura Cao) and Felix (Francisco Barreiro), disappear after they ascend a mountainous rock formation. When they peculiarly reappear the following day, the parents become concerned that their children may have been sexually abused during their disappearance but their strange behaviour eventually raises questions of a supernatural nature.

Ostensibly Spanish independent filmmaker Adrián García Bogliano, who was behind the Golden Hugo-nominated Cold Sweat (2010), is an advocate of replication and cliché. Following the disappearance of her children, mildly concerned Sol waits patiently at a garage, staring toward the unusual rock formation. She is soon joined by the illusive garage owner (Enrique Saint-Martin) who ominously tells her how “the Indians who lived in this area believed the hill had power […] it was considered a cursed place.” Aside from its banality, this scene echoes Victor Pascow’s stark warning in Mary Lambert’s screen adaptation of Pet Sematary (1989) but with the absence of impact or indeed foreboding that the earlier film so effectively offered. During a later moment of absurdity, the garage owner recalls how there is a connection between the hill and his daughter who “was the last victim of the worst serial killer we ever had.” Similar examples of appallingly lazy dialogue pervade the film and further compound the notion that Bogliano really has nothing new to offer contemporary horror fans. This film seems to employ every horror archetype possible, with the exception of Felix Barreiro who is serendipitously the only redeeming feature of this film. He creates depth through his portrayal of a devout yet flawed family man. In a bleak revelation during the film’s climax, he responds to a deeply traumatic moment with an intense and astounding realism. Although rising actress Cao’s performance is convincing at times, her role is punctuated by contradiction, resulting in a bizarre and illogical character. Both Martinez and Garcia never really succeed in arousing suspicion through their behaviour, which rarely exceeds that of stroppy pubescent children. In a highly exploitative introduction the film thrusts the audience into an anonymous bedroom where two female characters are making love. It soon becomes apparent that this scene serves absolutely no narrative function. The scene is used purely for gratuitous purposes as we later discover these characters are merely extras. In an interview with Bloody Disgusting magazine in July 2012, Bogliano criticised contemporary horror films for using a “very lazy approach. When they’re not showing something on the screen, they say they are making a Hitchcock kind of film.” Bogliano implied that he wanted to subvert preconceptions of the horror genre and provide something with a controversial edge that would shock audiences. In Cold Sweat Bogliano frequently alternated between close-up and extreme close-up of the tortured female body, effectively building tension and shocking the audience. By contrast, his latest occult offering has a flaccid plot and objectifies the female body in a cold, detached way through unnecessary sex scenes and extreme close-ups of breasts. It is quite possible for a horror film to provide a love scene that interweaves itself into the narrative and enriches the relationship with the characters in order to be both controversial and highly emotive. Indeed the graphic love scene between Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie in Nicholas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now (1973) is conveyed with absolute profundity. Bogliano instead chooses to blunder his way through the love scenes giving them the lustre of superfluity. Bogliano makes bold claims about his films but he has yet to provide originality or anything with much substance. Here Comes the Devil deals with some potentially heavy subject matter but its importance is evaded in favour of gratuitous noise. The result is a film that provides little more than a regurgitation of material previously used by respected directors of the genre. |