|

|

Capturing a meek wedge of seemingly ideal suburbia, picketed with its white fences and slick SUVs, the latest foray into adaptations of best-selling literature offers a glib and often perverse snapshot of modern-day relationships. Scripted by the novel’s author Gillian Flynn, fans of the book may feel unsatisfied as director David Fincher’s condensed memoirs of a marriage in peril ultimately feel coldly vacant.

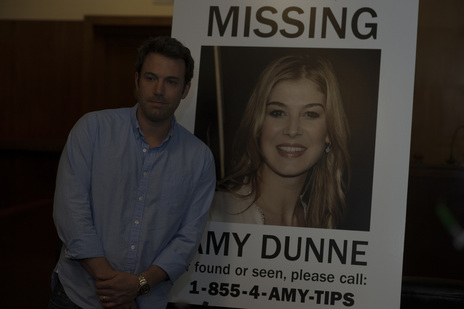

With Amy Dunne’s (Rosamund Pike) mysterious disappearance captivating the surveilling media’s eye, handsome husband Nick’s (Ben Affleck) innocence comes under scrutiny. The narrative shifts between time periods; pleasant memories of the past inform the present and dreary search for “Amazing Amy”, a sobriquet based on an ironic collection of SparkNotes that divulges Amy’s childhood life. Respectful to Flynn’s novel, Amy’s tale unfolds through diary snippets of an all too romantic past. That is, until worlds collide and the uneasy mystery unfurls to expose the imperfections of marriage, and warped impressions of love. Fincher casts a patchwork of cunning caricatures that cuts, thrusts and jousts at the throat of typecast roles. Romance in the modern age sounds less like the pleasant Operating System from Her (2013), and looks more like a hastily cleaned crime scene. Fincher’s off-kilter adaptation of Gone Girl is like a child’s dollhouse where the neat surfaces are far too perfect to be real. It has a sense of eerie canniness, a lack of empathy and a general spookiness in its masquerading of reality. Similar to American Beauty’s (1999) insistence to “look closer”, Fincher replaces the white fences with a roll of police tape, as the institutions of love buckle under the allure of sweet sex and deadly deception. Fincher taps into the cultural zeitgeist once again. Where The Social Network (2010) remarked on the (dis)connectedness of an intelligent yet arrogant youth in its stride, Gone Girl is a disarraying mess that mocks marital vows. It is a puzzle where nothing fits together, tailored for a culture where everything is uncertain. The crisp aesthetic, framed by cinematographer Jeff Cronenweth, wraps the scene in a clean sheet of plastic and preserves a distorted vision of the crime. The film is punctuated by an abusive soundscape courtesy of Nine Inch Nails’ Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross; its harsh hums contribute to a peculiar thudding score. Behind the vows of the perfect marriage, however, Fincher and Flynn conspire to interweave a running and ever-satirical agenda platformed by the disturbed couple. The film grapples with a mélange of thematic issues, situated at the core of many crippling cultural customs of society, exemplified by the growing media empire and, perhaps its most polarising of effects, debates around gender politics. Flynn’s verbalising of societal failings, via the story at the centre of the drama, straddles an overly dark and deluded physiological thriller embraced in her written canon (with Sharp Objects published in 2006, and Dark Places in 2009), with the snarky vocal chords of an often comical Chuck Palahniuk novella (Choke, for example, published in 2001, as well as Fight Club in 1996). Fincher, of course, envisions what should be a soulful community as haunted and horrific. An issue of debate that bubbles to the surface is just how saturated the news media can be, where it assembles fake narratives that solicit response from the general public. These are often endorsed by a roster of offbeat personalities, recalling the likes of Jeremy Kyle’s excessively judgemental jabbering. Meanwhile, Flynn beckons the audience to interrogate the on-screen information, to suspend truth in disbelief, and trust nothing and no-one. Not even your spouse. With Nick assuming the role of bemoaned husband, and Amy embodying a top-heavy fraction of craziness to bitchiness, Gone Girl gets more interesting in studying the interactions between gender. In the story of a marriage come undone, the plot finds traction in exploring victim culture. As the plot progresses and twists emerge, the spotlight shifts from Amy to Nick, husband to cold-blooded killer, the prosecuted to the victim, and victims into villains. Perhaps it is an elaborate critique of gender roles, or simply that popular audiences are too uncomfortable, unfamiliar even, to allow a woman to be anything other than the catalyst for her own abuse. But, Flynn’s neat categorising of characters – the “doofus husband”, as his sister Margo (Carry Coon) calls Nick, or the perfect wife with aspirations for children – focuses on the nightmares of what increasingly resembles gender warfare. The binary opposites of misogyny and misandry entertain two very different sides of a coin with much currency for debate. But, it becomes unclear as to the message at the heart of Flynn’s fragile glass bottle, bobbing atop an ocean of possibilities. |