Birdman

|

|

It seems entertainment is always fundamentally subjected to the lens of art. The presence of commercialism is said to nullify expression. The creative division that exists between the polar extremes of blockbuster action movies and highbrow theatre is an expanse for which few consumers care to suspend their tastes, who in their right mind could take an actor who played a superhero seriously on the stage? Birdman went on general release in the UK on 1st January after premiering at the London Film Festival in October and has since been met with a massively successful reception, raking it in at the box office and receiving fantastic reviews, not to mention nine Oscar nominations. Is it worthy of this almost disarmingly high praise?

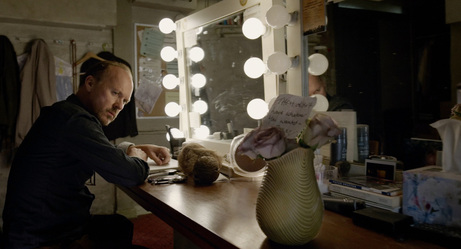

Directed by Alejandro González Iñárritu (credited here as Alejandro G. Iñárritu) whose previous directorial efforts include complex narratives Amores Perros (2000), 21 Grams (2003), Babel (2006) and Biutiful (2010), Birdman stars a wide ray of eclectic talent in Michael Keaton, Zach Galifianakis, Edward Norton, Emma Stone and previous collaborator Naomi Watts. Riggan Thomson (Keaton) is a Hollywood actor known across the globe for his portrayal of the legendary superhero Birdman, a role he walked away from in order to pursue his other ambitions. Specifically, Riggan desires to “do something important”, a desire which has resulted in the Broadway show What Do We Talk About When We Talk About Love that Riggan has written, cast, directed, produced and stars in. His attempts to carve himself out as a respectable artist seem to go unappreciated by everyone around him including his best friend and lawyer Jake (Galifianakis) who apparently only cares about lawsuits and money, his supportive yet exhausted co-stars Lesley (Naomi Watts) and Laura (Andrea Riseborough), the highly arrogant Mike Shiner (Edward Norton) who seems to only care about himself, and especially Riggan’s daughter Sam (Emma Stone) who thinks the whole production is part of her father’s midlife crisis. Given Keaton's career, the film enters new depths of tongue in cheek relevance. Perhaps the first thing you will hear about Birdman is its use of the single shot device for tracking highly complex sequences of dialogue as well as action, taking the audience along with the actors through the claustrophobic corridors of the rundown 800 seat theatre and out onto the draughty stage where the actors often embarrass themselves in previews of their troubled production. The constructed effect makes for a wonderful expression of realism, gorgeously showcasing the theatre platform as a space for “real acting”. The importance of achieving the “real” in performance is something that Mike obsesses with and Riggan seeks out as a measure of achievement, culminating in the film’s climax. The combination of comedy actor Galifianakis, Batman (1989) actor Keaton and The Amazing Spider-Man’s (2012) Gwen Stacy (Stone) already makes us expect something a little more zany than the usually sullen performances of Academy Awards favourites. Although Birdman is a dark comedy, the performances being delivered here are absolutely jaw-dropping. Acting, both off stage as well as on it, is dynamic, fluid and highly believable, only added to by the construction of long shots. The tactic is most memorably utilised in extended dialogue sequences, one of the most piercing and relevant of which, is likely the tirade venomously spat out by Tabitha Dickinson (Lindsay Duncan), a highly respected and widely feared theatre critic who is none too pleased by what she sees as Riggan’s undue transition from Hollywood to the niche drama circuit of Broadway. Her address to him in a local bar not only taps into Riggan’s deepest insecurities, directly from the mouth of the woman he aims so hard to impress, but also the state of American cinema itself. As blockbuster entries continue to command box office revenue and the lines between high art and consumerist trash continue to blur, an especially obvious threat around awards season. Yet, for all its commentary about the relationship between consumerism and art, techniques such as the long shot and cutting sound or music to sudden silence, have been widely praised in other Oscar winners such as Children of Men (2006) and Gravity (2013) and come across as rather transparent directorial decisions or even “Oscar bait”. The fascinating dichotomy between entertainment, creativity and the heartless criticism attached to it is challenged by the film’s apparently quite shallow mind-set to pander to populist Academy tropes. This strikes an ironic chord given the film’s reference to the tired, meaningless tropes present in action Hollywood; with explosions, guns and giant monsters being all the public want. Even Riggan's artistic obsession with "real" acting ends up becoming another populist trope by the end of the movie. The similarity between this shameless conventionality in Hollywood and repetitive cinematographic themes in Oscar winners tells us that the gap between the supposed creative elite and the cinema-going public are in fact laughably similar. |