Why so serious?

|

|

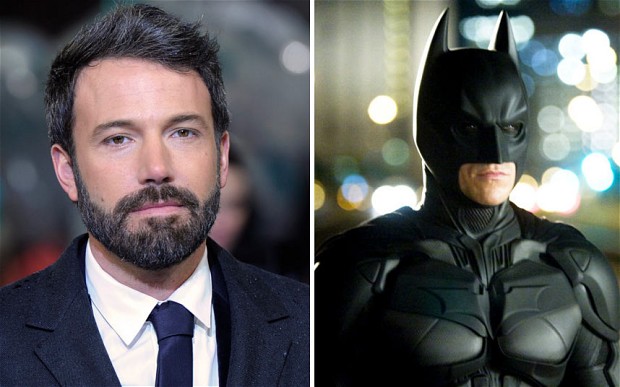

Hans Zimmer’s faint hum escalates into a sweeping roar, the camera pans and locks onto a lone figure above the bustling nightlife of the city below. Draped in blackness, with a cape flapping wildly with the wind, the mythic crusader waits, watches and protects. Joining the energetic and loud landscapes of Zack Snyder’s Man of Steel sequel, Kal-El, the already proven superhuman with a tendency to kick ass, will face off against the iconic Batman. You will probably have heard by now that Ben Affleck will be assuming the role of the latest caped crusader.

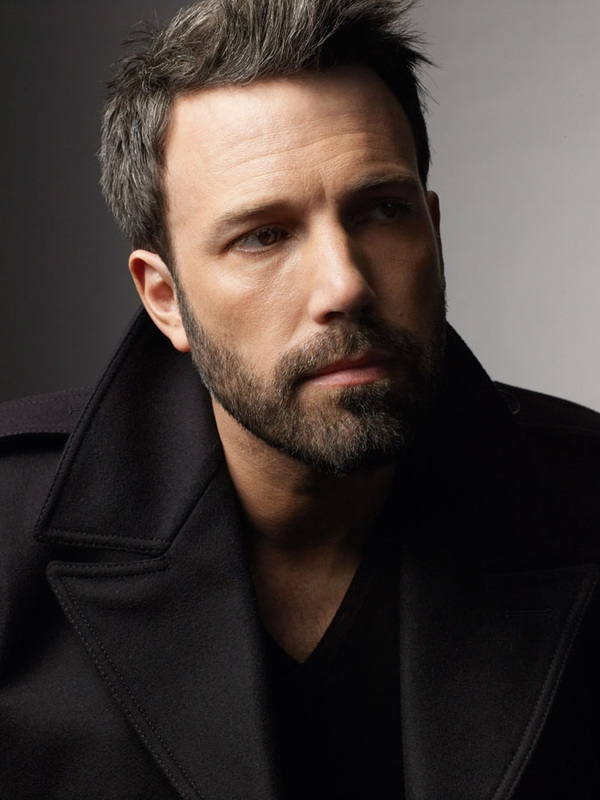

For some, these words may have an unsavoury aftertaste to them: Affleck as the Batman? Surely not. But, once upon a time, the star had an undeniable and enjoyable presence on screen, something human, determined and agitated in his days of Kevin Smith collaborations like Dogma (1999). His repertoire has since expanded with a range of good, bad and frankly ugly screen performances. In Michael Bay’s testament to the American fervour for “blowing up stuff”, the infamous and historical inaccuracy that is Pearl Harbour (2001) saw an all too familiar image of a groomed Affleck delivering an automated performance. In 2003, Daredevil saw Affleck don a tight and constraining red leather suit to play the blinded Marvel superhero. The young actor was mostly expressionless, terribly rigid and offered nothing more than a faltering and lifeless attempt to assume the dark role. Critics and audiences alike berated the star, leaving his repertoire forever tarnished by the burden of that mistake. In the same year, Gigli (2003) heralded a woeful and deprived performance from Affleck as the film tried to capitalise on the relationship between himself and Jennifer Lopez that was quickly becoming a media sensation. However, his persona is not entirely represented by his tendency to model instead of act and more recent roles have reignited faith in the actor’s capabilities. Time is beginning to heal the wounds of Affleck’s more hapless endeavours. In 2006 Hollywoodland saw his playing a depressed George Reeves, TV's Superman, yet his characterisation was enjoyable to watch. In State of Play (2009), Affleck’s appeal to the actorly held true to the twisting and turning of the political thriller. Affleck seemed to be more human in this role, even if it was for a brief and fading moment. In the following years, Affleck’s maturity resonated with a sweet and melancholy performance in The Company Men (2010). Yet Affleck continued in his struggle to be accepted as a serious actor type. His directorial efforts have been met much more favourably. The resounding success of The Town (2010) has helped to restore Affleck’s credibility. As both director and actor, his role was more sensitive and edgy. The subsequent Oscar success of Argo (2012) confirmed Affleck’s talent both behind and in front of the camera. This time a brooding and sympathetic agent with wild and overgrown jet-black hair, Affleck’s portrayal was both heroic and endearing. Now in his forties, Affleck’s repertoire features numerous meaningful performances, strong directorial efforts and now his third outing as a costumed crime fighter. Perhaps, Affleck’s calming presence will add to the humanity of Snyder’s fantasy; his maturity and sensitivity could make for a loveable Bruce Wayne and a refreshing Batman. Comic book heroes have come a long way from the sketchings on paper to the deep, humane and flawed characters with slick costumes that have been visualised in Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Night franchise (2005 – 2012). Zack Snyder’s latest creation embraces Nolan’s vision of a new breed of noir hero: the lone, complicated and troubled character. Both directors have helped to forge formidable myths into the popular cultural consciousness. The Batman has become more than just Bruce Wayne’s alter ego or a boy with many gadgets with a dark cave and swarm of bats, but a symbol. The costume, the name and the image establish one grand idea: the perseverance of hope. His image is characterised by a distorted and exaggerated suit, an unhealthy fetish for the colour black and a disturbed voice that complements the tone and equates his presence with fear. Batman is dissociated from his human counterpart, allowing him to become the beloved icon. His distanced self and inhuman image transgresses barriers to become a universal figure of triumph. Snyder respects this sentiment; there is something largely universal about heroes, an appeal that surpasses every test and boundary and withstands time. Snyder’s bleak reality in Man of Steel sought a connection to humanity embodied by Kevin Costner’s Jonathan Kent and the actors who portrayed the young Clark. Affleck’s everydayness, silent thoughtfulness and broodiness sits well with the realism Snyder is trying to construct and bodes well for the sequel. His measured restraint is likely to counteract the rapid pace, his humanity may frustrate the immortality of Cavill’s Superman, and his calm demeanour could change the tone of the destruction. Perhaps Ben Affleck can be that hero that Gotham deserves. |